Nº 2583 - Abril de 2017

Pessoa coletiva com estatuto de utilidade pública

In August 1963, the Portuguese prime minister, Dr. António de Oliveira Salazar, wrote a lengthy and optimistic letter to the South African prime minis-ter, Dr. H.F. Verwoerd, that arrived at an opportune moment, one in which South Africa was suffering international condemnation for its Sharpeville massacre and isolation with its forced departure from the British Commonwealth. On top of these two setbacks, the UN was considering the imposition of an arms embargo, hence Salazar’s letter was a bit of sunshine in an otherwise dark period.

Salazar and Verwoerd both agreed that the two nations were alone in defending Africa and Western civilisation from communism, and every form of cooperation with each other would be most advantageous1. While this view may seem myopic to the reader, austral Africa was, after all, perceived by the two leaders to be the hot front in the Cold War, and they felt keenly that their shooting war was far more different and dangerous than the posturing in Europe. Needless to say, there were other Cold War proxy conflicts in Latin America and South East Asia, but when you are the target, as these two were, your perspective is narrowed.

Portugal, in fact, needed South Africa very much, as continental Portugal or the metrópole was a long way from the African battlefields, and indeed, when help was required in the March 1961 Angolan emergency, South Africa had stepped forward to supply military matériel. In September, Verwoerd responded that South Africa was prepared to continue with defence cooperation, and in November, South Africa assigned a senior military officer, Brigadier Willem van der Waals, as its vice-consul to Luanda to strengthen the relationship2.

Angola was of particular strategic importance to South Africa, as its League of Nations mandate, South West Africa (SWA), lacked water and energy, two key ingredients for its development. It was a mineral-rich area, and South Africa wished to begin mining there. In October 1964, as the relationship blossomed, the two signed several accords regarding Angola, the most prominent of which was the one relating to the Cunene River and its hydroelectric project to supply power to SWA. These accords were the beginning of a mutually fruitful relationship that would cover the gambit of political, economic, and military issues, until 1974.

One of the most remarkable military aspects of this relationship was the development of the South African-Portuguese combined air support element of counterinsurgency as it was applied in the East of Angola. Portugal had attempted air envelopment in the north with paratrooper drops, as it had no helicopters in the opening years of the war. These were effective in reoccupation, but there was never an element of surprise, as the landing zones (LZ) had to be marked in advance, and the approach of a flight of transports could be heard by the insurgents well ahead of the drop. On the other hand a flight of helicopters following a nap-of-the-earth approach to shield their noise could arrive almost unheard to a previously scouted LZ and truly surprise and overwhelm an enemy group, particularly when supported by a gunship. The French had developed this tactic in Algeria, and the Portuguese were actively seeking to bring it to Angola. The helicopter choice in this tactic was the five-man French Alouette III; however, none were available in 1961 in Angola. As they did become available between 1961 and 1966, so tactics evolved. The “Alo”, as it was called, became the basic counterinsurgency fighting tool in Angola. It was relatively slow, seemingly fragile, but nonetheless, remarkably resilient, and reliably hauled its crews into combat and returned safely.

Meanwhile, in 1965, the east of Angola became active with insurgents whose activities were aimed at both South Africa and Portugal. This emerging threat drew the two countries together, and this is the story of how these culturally contrasting forces combined their resources and efforts to execute effective operations that stalemated their enemies in a successful counterinsurgency campaign.

Following World War Two, nationalist sentiment grew within the native population in Lusophone Africa; however, nationalist movements were largely urban and were thus in a hostile environment for two reasons: the majority of their opponents lived in cities, and the national police or International Police for Defence of the State (Polícia Internacional de Defesa do Estado or PIDE) operated most effectively there. Consequently, they were either short-lived or dormant3. By 1956, the young Marxists of the Angolan Communist Party contributed to the formation of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, or MPLA). The MPLA developed roots among the urban population, and these roots were composed largely of mestiços (mixed race peoples), who controlled the party. The movement had little in common with the rural peasants of the east and south of Angola and made little effort to gain their devotion. In December 1956, the initial MPLA manifesto was published publically, and predictably PIDE reacted unsympathetically. Prominent MPLA leaders were forced to flee into exile, and from 1957 onward PIDE action was so successful that the MPLA was unable to maintain more than the most rudimentary organisation inside Angola4. The MPLA was forced to conduct its affairs from neighbouring states and was isolated from any of its cadres within Angola.

The MPLA in exile established itself initially in Léopoldville and aligned itself not only with other independent African nations and their socialist philosophy but also with the communist bloc. In 1962, the MPLA formed its military wing, the Popular Army for the Liberation of Angola (Exército Popular de Libertação de Angola, or EPLA), to project its influence into Angola. This nascent force numbered between 250 and 300 young men who had undergone military training in Ghana and Morocco. The EPLA sought to expand the conflict across the northern border of Angola with this force and penetrate the entire country, but found itself in competition with the other prominent Angolan nationalist group at the time, the Union of Angolan Peoples (União das Populações de Angola, or UPA), also resident in the Congo, for acceptance as the leading representative of the Angolan people. The UPA, through its influence with the Congo leadership, forced the MPLA to leave Léopoldville in 1963 and re-establish itself in Brazzaville, from which it was difficult to conduct a campaign across an unenthusiastic third country and into a now distant Angola. As a result, northern Angola proved to be barren for the MPLA, and it was not until 1966, with the opening of its second front from Zambia, that some success would come.

The UPA was formed in the mid-1950s from a number of small disparate groups, and leadership was passed to Holden Roberto in 1958. UPA strength rested in the rural populations of the Bakongo ethnolinguistic region of Angola. These people straddled the border area that reached into the Belgian Congo, Angola, Cabinda, and the French Congo, the footprint of the ancient Kongo Kingdom. Roberto unequivocally held the view that not just a “Bakongo Kingdom” or some other entity but all of Angola must be freed. The UPA was able to develop a following in the north of Angola because of the relatively open frontier, and this loyal cadre became the basis for the devastating uprising in March 1961. Portuguese presence in this area took the form of chefes do posto (heads of posts) and administrators, as opposed to PIDE, and these officials were so sparse that it was physically impossible for them to maintain anything but the most casual control over their districts5.

The UPA formed its military wing, the Army of National Liberation of Angola (Exército de Libertação Nacional de Angola, or ELNA), in June 1961 after the March attacks did not achieve a Portuguese capitulation, as in the case of the Belgian Congo. Roberto as its commander-in-chief proved unsuccessful both as a leader and strategist. He was so “fiery-tongued” and autocratic that he would accept little more than arms and money and was unable to use either with good effect6. According to van der Waals, without training, the ELNA “set a demoralising example of politico-military incompetence and indiscipline” and “involved itself in military activities in the narrowest sense (...) but avoided contact with the Portuguese security forces as far as possible”7.

This lack of direction caused great rifts in the UPA leadership. Despite the UPA reorganisation in March 1962 at the behest of Joseph-Desiré Mobutu (later from 1972, Mobutu Sese Seko), president of the Congo, to include additional groups, to rename itself the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (Frente Nacional de Libertção de Angola or FNLA), and to establish the Government of the Republic of Angola in Exile (Governo da República de Angola no Exílio or GRAE), little of substance was accomplished. A frustrated Jonas Savimbi, Roberto’s “foreign minister” and an Ovimbundu, formally broke with the UPA/FNLA in July 1964 and formed the third nationalist movement in Angola, National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola or UNITA). Savimbi publically announced his break at the 1964 OAU meeting in Cairo, Egypt, and began his campaign against the Portuguese from western Zambia. The next year, Alexandre Taty, “minister of armaments,” after challenging Roberto in an unsuccessful coup, defected to the Portuguese in Cabinda with a substantial number of his followers.

The ability of the MPLA to operate militarily in Angola became almost completely constrained by November, 1963, and it looked increasingly isolated. In January 1964, at its Conference of Cadres (Confêrencia de Quadros) in Brazzaville, it was decided to rebuild the movement as a serious revolutionary force by opening a front in the east of Angola through Zambia. The MPLA had made overtures to Kenneth Kaunda, the first president of Zambia following its independence from Britain in 1964. It had also befriended Julius Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania, likewise following its independence from Britain, in 1962. Fortuitously, in 1965, Tanzania and Zambia permitted the transit of Chinese and Soviet weapons and MPLA fighters across their territories to newly constructed bases adjacent to the Angolan border. This enabled the MPLA to open a major offensive and to conduct an intensive insurgent campaign in the eastern Angolan districts of Moxico and Cuando Cubango. By the opening months of 1966, proselytising of the population in the east was evident to Portugal, and in April the first armed MPLA incursions occurred. Indeed, PIDE saw this as part of the Fayek plan conceived by an Egyptian in 1964, which advocated simultaneous insurgent thrusts from Zambia aimed at South Africa, Rhodesia, Angola, and Mozambique8.

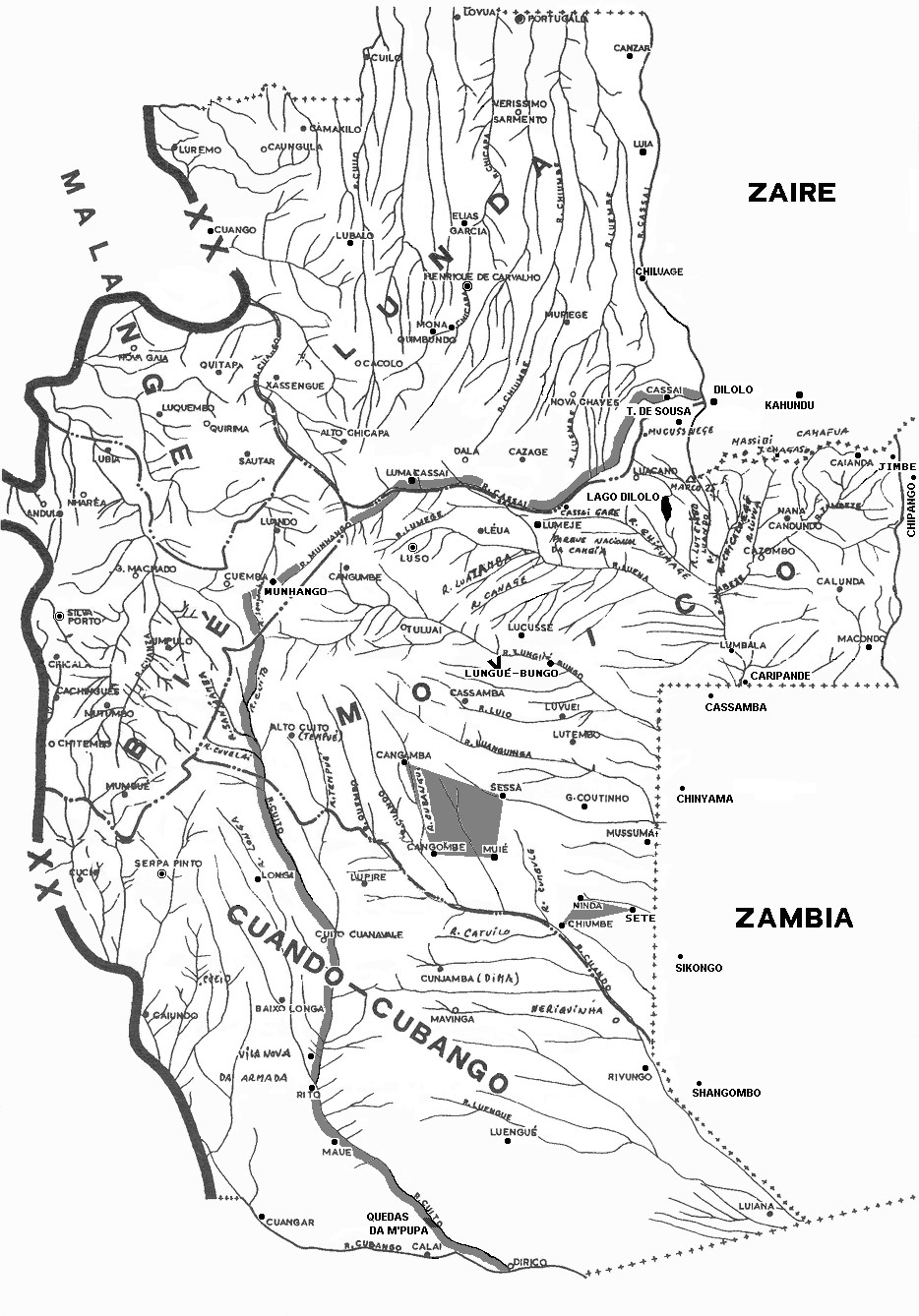

The MPLA planned a two-pronged assault. The southern one would be mounted from its Zambian bases of Mongu, Shangombo, and Sikongo and known as the Route of the Cuando (Map 1). It would follow this river valley westward with the plan of reaching the populated and wealthy district of Bié and the central plain of Huambo, the heart of Angola. From this point, the insurgents hoped to control the entire country and to reach all the way to Malange through an axis of advance along the Cuanza River valley9.

The northern one was called the Route of the Luena and was to be launched from its Zambian bases of Chipango and Cassamba and aimed along this river directly at Luso and from there to the highland plain of Malange. The hope was to gain control of the Luanda-Malange railway, reach Luanda, and link with forces coming from the north10. In fact, these routes never successfully penetrated the Portuguese front defined by an interior line connecting the population centres of Cazoa, Cazage, Cassai-Gare, and Lucusse with Luso as its hub11. The MPLA could muster about 4,000 men, of whom about 3,000 were armed. Its operations were centred on anti-vehicle and anti-personnel mines, forced recruiting and intimidation of the population, reaction to Portuguese operations, and some bursts of fire at Portuguese military installations in hit-and-run tactics12. Equally as dangerous for the Republic of South Africa were the South African People’s Organisation (SWAPO) insurgents, likewise operating from Zambian bases and transiting the southeast of Angola through Cuando Cubango to the Caprivi Strip and Ovamboland, border areas of SWA.

The question of SWA had its origins in the partitioning of German possessions following World War One. Known then as German South West Africa, it was given to South Africa as a League of Nations mandate. The territory was vast at 823,000 square kilometres and had a population of about one million, or a density of 1.2 people per square kilometre. SWAPO was originally a labour organisation, the Ovambo People’s Congress (OPC), which was formed in 1957 to contest the migrant labour system in which thousands were hired under a two-year contract to work in other parts of SWA. It was a primary grievance, as it was administered without much compassion or interest in the workers’ welfare and was a target for condemnation by many organisations13. The OPC shift of focus from labour abuse to independence came on 10 December 1959, when the authorities decided to relocate the residents of a long-standing black-populated area of Windhoek, known as “Old Location”, to the new township of Katatura further from the city centre. A large group of residents gathered to confront the authorities, and while the police tried to disperse the crowd, they were unsuccessful and in the end opened fire. Eleven were killed in the incident and fifty-four wounded14. The next year the OPC became SWAPO in an attempt at a broader appeal15. In 1962, SWAPO located its headquarters in Lusaka and founded the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN)16. This meant that there would be a shooting war.

The first PLAN infiltration from Zambia occurred in September 1965 with six trained insurgents slipping over the unguarded Angola-Caprivi border. Except for surveillance, little action was taken. In February 1966, a second small group managed to murder two shopkeepers and an itinerant Ovambo in Angola, believing that it had crossed the border. The group dispersed, and three of its members were eventually arrested on tips from local inhabitants. In July 1966, a third group crossed and attacked tribal chiefs, white farms, and a border post. The South African reaction was swift and decisive, as on 26 August helicopter-borne troops knocked out the nascent SWAPO base at Ongulumbashe in SWA and killed two, while rounding up fifty-four. It was the only SWAPO base ever to be established on South African soil. In early 1968, PLAN began new infiltrations from Zambia into east Caprivi. By March, there were a total of 160 insurgents behind bars in South Africa. In October, two large groups slipped in from Angola and restarted the insurgency. Reaction was again swift, and fifty-six insurgents were captured, while the rest fled over the border17. The nearly deserted Cuando Cubango district of Angola was now clearly a transit area for PLAN, and this situation set the stage for further cooperation between Portugal and South Africa.

The Eastern Military Zone (Zona Militar Leste or ZML) of Angola was a vast plateau of some 700,000 square kilometres that comprised the districts of Lunda, Moxico, Bié, Cuando Cubango, and portions of Malange18. It was a wasteland for insurgent proselytising, as there were only 1.3 million inhabitants in this eastern theatre or about five people per square mile. This latter figure was misleading, as the bulk of the population lived along the Benguela Railway (Caminho de Ferro de Benguela or CFB) or in the primary towns, so in the bush there was actually less than a person per square mile.

Overall the ZML was a sprawling savanna sparsely dotted with trees. From the point of view of the insurgent, there were ideal concealment areas scattered through the more elevated terrain characterised by ravines and dense forest19. Both the vast savannas and mountainous topography posed significant policing problems for Portugal, for it meant that finding an insurgent column or small “squadron” in either setting was extremely complicated, and gathering the vital intelligence about its activities and intentions was an extraordinary challenge. Because the ZML was a big place and moving the needed troops to contact with the enemy and supporting them was difficult, the key was the mobility and flexibility provided by airpower.

Not only was the battlefield vast, but belligerents operating there had to negotiate a significant variable, the harsh weather. The rainy season in the east ran from October to March and left enemy columns wet, miserable, and mired. Conversely, it could severely affect flight operations with its electrical activity and towering cumulonimbus clouds. This was followed by a dry, cool season characterised by heavy morning fog, the cacimbo, which was caused by the long and chilly African nights. This fog hid the insurgents and invariably hampered flight operations.

In countering a multi-axis assault, the Portuguese were quick to see that UNITA and the UPA/FNLA in the east were limited threats and that the MPLA represented the real danger. Hence, they developed a three-phase theatre strategy of first checking the expansion of the insurgent penetration by blocking the MPLA and limiting its fighters to a geographic area bounded by the Cuito, Cuanza, Munhango, and Cassai Rivers. This was essentially a line running from Dirico in the south to Teixeira de Sousa in the northeast. The area between this line and the border with Zambia was admittedly a substantial tract, but it was thinly populated by any standard and would provide little sustenance to the invaders. The insurgents could thus do little damage in this isolation and would indeed slowly starve. Within it security forces would relentlessly pursue an increasingly harried and besieged enemy. Finally, in 1973 and 1974, as the cordon drew progressively tighter, the enemy would be completely destroyed20.

Of deep concern to South Africa, moreover, was the mixing with and mutual cooperation between the MPLA and SWAPO insurgents in south-eastern Angola, and this Portuguese plan needed to address that threat. South African anxiety on this point was always prominent in discussions between the two allies.

On the tactical level, the first meeting between South Africa and Portugal occurred on 29 December 1966 at Cuangar and was prompted by the several groups of UNITA fighters operating in Cuando Cubango with the potential to aid the transit of SWAPO fighters. South Africa was deeply concerned at the deteriorating security conditions in this eastern third of Angola. The gathering consisted of several Portuguese Army officers, a PIDE inspector, and a contingent from the South African Police Service (SAPS) led by a Colonel van Wyk. Following an extensive Portuguese briefing on the intelligence gained from a captured UNITA prisoner, the South Africans unexpectedly suggested that the two countries cooperate militarily and that South Africa make some Alouette IIIs of the South African Air Force (SAAF) available to Portugal. These would be troop transport helicopters operated by South African pilots and aircrew and flown without national markings of any kind. The helicopters would be supported by South Africa with munitions and other matériel judged necessary for “the struggle against the terrorists that are our common enemy”21.

Both countries were quite sensitive about their controversial international status and sought to avoid any publicity about the defence of their territory against the several nationalist movements. Reporters and journalists were carefully screened and monitored, and their access to combat areas and troops could be restricted depending on their reputation for editorialising their news. Cooperation between Portugal and South Africa was thus circumspect and guarded. In areas where there were mixed forces, aircraft of both nations were devoid of national markings. This likewise extended to uniforms and the other paraphernalia of war. SAAF personnel, for instance, wore Portuguese uniforms when operating in Angola. Such cosmetics, however, were unlikely to fool a knowledgeable observer.

Surprised by the South African initiative, the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Angola, General Amadeu Soares Pereira, sent a secret note to Lisbon, on 28 January 1967, to Horácio de Sá Viana Rebelo, the Minister of National Defence, asking for guidance on replying to Pretoria. Rebelo, who was at the time visiting Guiné, responded belatedly on 20 February in a note that agreed completely22.

At Pereira’s weekly meeting with his commanders in Luanda on 11 September 1967, General João Manuel Soares de Almeida Viana, Commander of the 2nd Air Region (Angola) and formerly the military attaché to South Africa, summarised in a few words the problem that faced them – the escalation of the war in the east and southeast of Angola: “The gravity of the situation commands unusual solutions, such as asking South Africa for the maximum that it can provide”23. Despite Rebelo’s reticence on policy guidance from a distant Lisbon, contact with the South African military continued to gather momentum locally, and the PIDE office in Angola developed an issue paper to guide discussion. On the South African side, it was also the police – those assigned to duties in SWA and guided by senior army officers – who took a prominent and secretive role. The SAPS, which was responsible for border security, viewed the policing of SWAPO columns in Angola before they reached South African territory as a part of policing its own border, so it was keenly interested. Indeed, this tactical view reflected a larger strategic one in which South Africa saw Angola, Rhodesia, and Mozambique as buffers and aimed to keep any fighting distant from its borders through aid to Portugal and Rhodesia.

Pursuant to the contacts in late 1967, Viana again broached the topic of South African aid in Pereira’s first weekly staff meeting of 1968. After a visit to Luanda by SAPS elements, Pereira proposed to send a Portuguese delegation in great secrecy to Rundu, a small town and military base on the SWA-side of the Cubango River in the Capivi Strip opposite the Portuguese town of Calai. Although it was agreed that any military support by Pretoria would be discrete, Lisbon hesitated, and the visit was cancelled at the last minute. Conversely, Viana briefed Rebelo that the 2nd Air Region did not currently have the capacity to operate additional Alouette IIIs, and at the time could allocate only two to three helicopters and their crews for the immense ZML. On the other hand, South Africa, with minor adjustments in its operations, could spare up to ten Alouette IIIs with their crews and the needed logistic support to operate in Angola from airfields at Neriquinha and Cuito Cuanavale24.

In a new development, the bilateral meeting cancelled in January was rescheduled for 1–2 March, and the report on this meeting was the topic of continued discussion at Pereira’s first March staff meeting. Here he established the tactical and operational framework for military cooperation between the Portuguese and South African armed forces. In executing this plan, the men of the FAP and SAAF were to perform with great distinction.

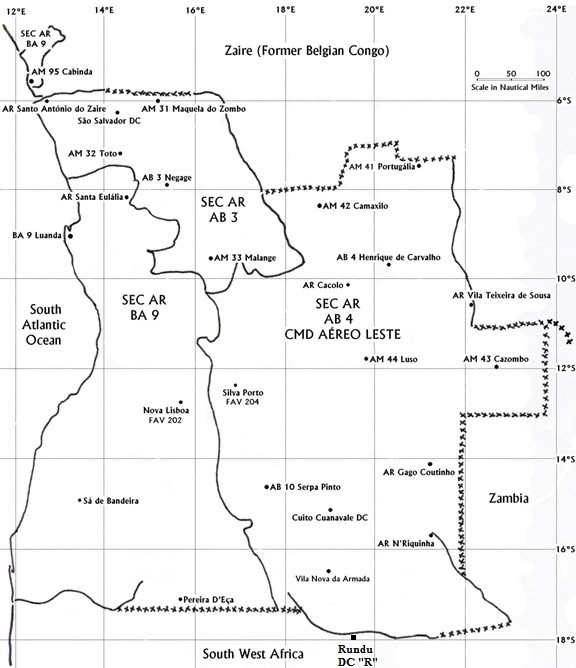

The Portuguese Empire was apportioned into three Air Regions (Região Aérea or RA), which were administratively and geographically manageable divisions based on geopolitical considerations. The 2nd Air Region, the focus of our attention, comprised Angola and the strategic islands of São Tomé and Príncipe and had its headquarters at Air Base 9 (Base Aérea 9 or BA 9) in Luanda. BA 9 was the prime airfield in Angola and the centre of a spoke-like network designed to bring the umbrella of air support to the ground forces and population and enable decentralised operations (Map 2)25. This Air Region was divided into three Air Sectors of Operations (Sector Aéreo de Operações or SEC AR), each identified by its primary airfield in the spoke organisation. While BA 9 was a “full service” airfield, airfields with only essential services were classified as Aerodrome Bases (Aeródromo Base or AB):

1. SEC AR AB 3 (Negage);

2. SEC AR AB 4 (Henrique de Carvalho); and

3. SEC AR BA 9 (Luanda).

The boundaries of each SEC AR overlaid those of the ground forces.

By 1967, it was clear that SEC AR AB 4 would be the centre of Portuguese-South African cooperation, as insurgent penetrations would increasingly come from the east and Zambia and not the north and the Congo. Unfortunately, AB 4 was poorly positioned in Lunda, north of the developing war in Moxico and Cuando Cubango, and its dependency bases to the south were better positioned to address the new threat. Resources were consequently poured into their expansion to support the full range of air operations now required in the southeast. There were nine dependency airfields of AB 4, six of which were located in the east and southeast and positioned to contest the lines of enemy infiltration. They were variously identified as either Alternate Aerodromes (Aeródromo de Recurso or AR) or Maneuver Aerodromes (Aeródromo de Manobra or AM): Luso (AM 44), Vila Teixeira de Sousa (AR), Cazombo (AM 43), Gago Coutinho (AR), Cuito Cuanavale (AR), and Neriquinha (AR). These were the most active in supporting ground forces and the population, and were initially little more than dirt strips in the wilderness. However, with South African help they were expanded substantially. In 1969 and 1970, as South African support gathered momentum, Lieutenant General Charles Alan “Pop” Fraser, the General Officer Commanding – Joint Combat Forces (GOC JCF), paid a number of visits to Luanda and coordinated the financial and physical SAAF support that expanded the runways at Luso (asphalt, 7,875 feet by 130 feet), Gago Coutinho (laterite, 6,750 feet by 98 feet), Cuito Cuanavale (asphalt, 7,600 feet by 100 feet) and Neriquinha (earth, 6,750 feet by 98 feet)26. Improvement of these latter two permitted the Noratlas and the SAAF C-130 Hercules to land. While South Africa likewise helped with buildings, furniture, communication suites, and personnel to operate the facilities, the real heroes were the men of the FAP Directorate of Services and Infrastructure, who laboured for months on end to carve air bases from wilderness27. Reflective of this, Colonel Silva Cardoso remarked in 1972 on visiting an AR, “One day I landed and stayed for two days in Cuito Cuanavale at its enormous airfield with the capacity for every type of aircraft”28.

In February 1968, South Africa agreed to support Portugal with five Alouette IIIs and later increased this to eight and four Cessna 185s, all which would be assigned to an air detachment based at Rundu and flown by SAAF pilots. This much needed help bridged an important gap, as Portugal had only the odd helicopter in the east at the time. By the end of 1970, gifts from South Africa and purchases from the manufacturer enabled the FAP to allocate twenty-four of its Alouette IIIs to the east, and by 1974 this allocation had increased to thirty-six29. In the meantime, Portugal was to rely heavily on SAAF aircraft and pilots.

Coincidently, Portugal and South Africa established two aviation command centres, one at Cuíto Cuanavale and the other at Gago Coutinho, both of which were freshly built facilities. These were termed Joint Air Support Centres (JASC) in English and Centros Conjuntos de Apoio Aéreo (CCAA) in Portuguese. At each of these Portuguese airfields, South African aircraft, pilots, maintenance personnel, and communication specialists were temporarily deployed to support Portuguese operations30. This aid and the combined operations that followed from the Angolan airfields were aimed not only at disrupting SWAPO columns attempting to penetrate SWA but likewise enabling the SAAF pilots and aircrew to gain combat experience31.

By March 1968, the first directives covering air support were in place, and South Africa, in addition to its support operations from Rundu, agreed to gift an entire helicopter squadron of Alouettes to be stationed in the east at Henrique de Carvahho with a detachment in Luso. In mid-June, SAAF C-130 Hercules transports delivered the first five Alouette IIIs to Cuito Cuanavale for what was to be Squadron 402. These were quickly followed by two more, in July and another two, in August32. Ultimately this gift of “Alos” grew to seventeen without the traditional national markings or serial numbers in order to protect the relationship and its secrecy. In FAP records, this series beginning with 9317 became known as the “Black Block” of helicopter serial numbers, because they “did not exist”33.

The first operational SAAF flight into Angola was launched from its detachment at Rundu Air Force Base, on 16 April, in an Alouette III commanded by 2nd Lieutenant Peter Wilkins. The familiarisation flight was described as a reconnaissance mission, and it lasted three days. It followed an itinerary that began at Mucusso on the South African border, and included stops at Santa Cruz do Cuando on the Zairian border, Neriquinha on the Route of the Cuando, Gago Coutinho, and Cuito Cuanavale before it returned to Rundu. For reasons of security, the flights were described with some humour as “livestock research”34. On his return to Rundu, Wilkins and 2nd Lieutenant John Marais in a second helicopter were asked to conduct a night medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) of a Portuguese soldier gravely wounded in an ambush north of Luiana, an outpost dangerously close to the Zambian frontier. This mission began with a lengthy and trying two-hour flight of two hundred thirteen kilometres over the desolate Caprivi Strip with no visual references or radio navigation aids. The two helicopters landed at Bwabwata in western Caprivi, and in order to avoid the possibility of a collision flying in formation at night, only the Alouette III with Wilkins and his crewman Sergeant Harmse continued into Angola. The radio of the Portuguese patrol with its casualty was inoperative, and thus the soldiers started a bonfire to guide the aviators for a successful evacuation35. These and later SAAF incursions into Angola from Rundu and Katima Mulilo at the eastern end of Caprivi Strip were not yet a part of what would become the formal detachments operating from the two JASC/CCAA facilities.

In April 1968, Fraser again visited Luanda to confirm helicopter deliveries and to inform Viana that the SAAF would offer direct operational support in the frontier region of Moxico province, generally in Cuando Cubango province, and in the latter specifically in a defensive line reaching from Gago Coutinho, through Ninda, and to Chiúme. This line lay across the preferred access from Zambia to the Route of the Cuando.

For Portugal at this time, the top priority was the north, and while Viana estimated that he would need between twenty and thirty Alouette IIIs in the east, he could do little to meet that requirement. Currently, he had only fifteen helicopters in all of Angola, eight of which were gunships and could not carry troops. Of the fifteen, two were grounded with combat damage, two were in rework, and four awaited various repairs – an availability of 47 percent36. So, Portugal desperately needed SAAF support.

In May 1968, the SAAF established its 1st Air Component (1AC) at Rundu to support SAP units policing the border areas at the time, and its aircraft consisted of Cessna 185s, Alouette IIIs, and the occasional Dakota37. From this inventory the 1AC allocated four Cessna 185s and eight Alouette IIIs for support of Portuguese operations. These joint operations were coordinated by the Mobile Air Operations Team at Rundu, and the first mission occurred on the morning of 18 June, when Lieutenant Vic Swanepoel and his crewman, Sargent Venter, departed Rundu in the lead Alouette III in a flight of five headed for Cuito Cunavale. The aircrews spent a week familiarising themselves with the eastern Angolan operating environment, and two weeks later, on 4 July, moved Portuguese troops with the protection of a FAP gunship in an assault on an enemy camp near Rivungo on the Zambian frontier. Later, on 10 July, the SAAF helicopters performed the same duties in the vicinity of Ninda and Neriquinha. At the end of deployment they returned to Rundu for a week of rest and refitting38. On 17 July, the SAAF again supported Portuguese operations with a flight of three Alouette IIIs and returned on 21 July to Rundu39. Such operations were increasingly overseen and supported by a SAAF liaison and support staff housed at the primary airfields in Angola in a move toward decentralisation to gain flexibility.

Decentralisation of air operations was needed to adjust to the increased enemy activity. This now allowed resources to redeploy rapidly in support of ground forces and the shifting local battlefield environment. In addition to hosting SAAF detachments, the facilities were the home of FAP detachments of light aircraft, such as Austers, Dorniers, and sometimes T-6Gs, under the command of a junior officer. These were known as Detachments of Cooperation (Destacamentos de Cooperação or DCs), and they performed the everyday tasks of general transport, evacuation of wounded, visual reconnaissance, and sometimes armed reconnaissance in the frontier areas. Their operations supported Portuguese troops operating within a radius of the DC consistent with the operating capabilities of the aircraft available40. SAAF helicopters and personnel augmented the DCs routinely for operations, particularly in the dry season when enemy activity was at its height.

At Cuito Cuanavale (DC “C”) and others in the extreme south where the South Africans operated, it was necessary that commanders speak English or the South Africans speak Portuguese, a condition not always met. Indeed, as Lieutenant José Augusto Queiroga noted, the South Africans had very different dietary and cultural habits from the Portuguese that included speaking Afrikaans – the language of the Boer with its Dutch origins. Briefings were in English, but otherwise each national spoke his own language41. Despite this apparent barrier, the aircrews shared a love of flying and were proud of their skills. Young and fearless, they were able to operate long hours with little rest and became experts in tracking insurgents from the air.

The six DCs, all in the east, were:

– DC “H” at Henrique de Carvalho;

– DC “L” at Luso;

– DC “CAZ” at Cazombo;

– DC “G” at Gago Coutinho;

– DC “C” at Cuito Cuanavale; and

– DC “SP” at Silva Porto42.

As the relationship advanced, the SAAF missions ferrying Portuguese troops to engage the enemy columns in south-eastern Angola proved less that effective. As Wilkins put it, the regular Portuguese soldiers were conscripts with a two-year obligation to serve in Africa and were largely unaware that the “Dark Continent” even existed. These youngsters were not interested in a colonial conflict and certainly not in looking for a fight. Some were so inept at field craft that they could easily misread a map and trek in the opposite direction from the targeted insurgent camp after being deposited in the LZ. This meant that a pick-up after a supposed firefight required much patience and extra fuel to search for missing troops43. The offensive against the insurgents required capable soldiers and not these conscripts.

In December 1968, Fraser complained to the Portuguese that SWAPO insurgents continued to pass unhindered through the areas of Rivungo and Luiana on the Zambian border44. His and his airmen’s frustration with Portuguese troops and their lack of aggressive enemy pursuit following a SAAF insertion was expressed in no uncertain terms:

Portuguese soldiery wish to be dropped almost on their target area by our helicopters. The fact that the terrorists can hear these helicopters over a distance of up to ten miles, quite apart from the danger to our own helicopters, results in abortive attacks on terrorists bases deserted except for old men, women and children. It has been known, too, that on occasion troops were dropped at a distance of ten miles from a target and found, three days later, after having walked only half way45.

Fraser’s frustration was reflective of a conscript army that tended to avoid sectors where enemy action was reported, and failed to conduct follow-on reconnaissance operations to evaluate results, collect intelligence, and interrogate prisoners. Even when aided by close air support (CAS), conscript troops would produce fantasies of inflated body counts and numbers of captured weapons. Fraser wanted elite troops who would pursue the enemy: “In my view the military role must be performed by a comparatively small, elite, highly trained, lightly equipped and aggressive regular army of mature soldiers on their flat feet, together with a supporting air force to give it logistic support, strategic mobility and sometimes, a degree of tactical mobility – when the element of surprise is of secondary importance”46. Viana consequently agreed to assign a company of paratroopers or “paras” each to Gago Coutinho and Neriquinha47. Again in Wilkins’ words, the commandos and paras meant business48.

With SAAF help now becoming routine, the military command in Angola sought to “define responsibilities and establish procedures for the planning and execution of the support provided to Portugal”49. Accordingly, from January 1969, “external aid” from a “friendly country” was defined in a series of documents with terms used to disguise any link to South Africa, and even Rundu was identified simply as DC “R”50. These documents identified the four areas of aid:

1. Air support in the southeast of Angola;

2. Loan of five Alouette IIIs;

3. Supply of divers matériel; and

4. Delivery of aviation and vehicle fuels,

and defined the operating area for the SAAF with the following boundaries:

1. North, the Lungué-Bungo River;

2. East, the frontier with Zambia;

3. South, the frontier with South West Africa; and

4. West, the meridian through the SWA-Angola frontier town of Cuangar51.

The SAAF Cessna 185s operated from Luso (DC “L”) and Serpa Pinto (DC “SP”) and flew the typical missions assigned to light aircraft: visual and photographic reconnaissance, troop transport for assault, cargo transport, and MEDEVAC. The SAAF Alouettes flew primarily assault missions and were protected by a FAP gunship assigned from either DC “C” or DC “G”52.

Also in January 1969, the mission of the JASC/CCAA was formerly articulated in a top secret document, of which there were only thirteen copies, as the “organ responsible for the planning, coordination, and assistance for all of the activity of the DC “R” in Angola”53. Likewise, its manning was established as a major or captain FAP aviator, an army officer, various support personnel, a PIDE inspector, and a SAAF Air Liaison Officer. It was to function as an arm of the staff of the Commander-in-Chief of Angola to direct the SAAF support missions originating in Rundu and coordinate these with the Air Liaison Officer in Cuito. The JASC/CCAA also assumed logistic responsibilities (messing and berthing) for the SAAF crews and the security of their aircraft and equipment on the exposed airfields in the south of Angola. Lastly, the JASC/CCAA was tasked with providing a daily activity or situation report (SITREP) containing pertinent information on operations and developments in its area of responsibility (AOR) that were of interest to the Commander-in-Chief and the Commander, 2nd Air Region54.

This document expressly referenced the original loan of five Alouette IIIs from the “friendly country” and noted that they were furnished without national markings. These helicopters and subsequent deliveries were nominally assigned to Squadron 94 in Luanda and were to be used without restriction. Portugal was responsible for their maintenance, although the SAAF furnished their spare parts shipped to Luanda in crates cryptically marked “B9H93” – meaning Base 9, helicopter series 93, the “Black Block” – to shield them from any indiscrete eyes55. South Africa also became a major supplier of aviation fuel, and Rundu became the centre of South African support for Angola. From 1968 until the end of the war, one could observe the nearly constant stream of FAP Noratlas and Dakota aircraft and SAAF Transall and C-130 Hercules aircraft landing and launching at Rundu and throughout the east of Angola.

In the first seven months of 1969, Alouette III operations were launched from Rundu into south-eastern Angola and conducted from airfields there. Normally, the detachments were three to four weeks duration, and the pilots participating were briefed that all such missions were classified “top secret”56. The missions were coded in series: Operation Bombay (1969-1970), Operation Mexa (1971), Operation Atilla (1972), and Operation Resgate (1973), and all understood that there was to be no mention whatsoever of these, even in any aviator’s personal flight-hour logbook. South African Aloutettes would usually set out from Rundu in a flight of six marked only with large yellow letters from A to F as identification. The five troop carriers would form a loose “V” formation with about a kilometre spacing, and the lone gunship would slot into the “V” to keep all in view. The gunship was the slowest with the weight of its weapon and ammunition and thus its pilot would dictate the power settings for the others to use in maintaining formation. Indeed, weight was always a problem transiting into Angola, as each helicopter was loaded with two crews and their personal arms, uniforms, articles of personal hygiene, combat rations, and several dozen litres of water for each crewman, as water was quite scarce at their destinations57.

SAAF helicopters were supposed to participate in transport operations only, and these were conducted under the oversight of Major Gert “Jolly” Oosterhuisen, who was the Air Liaison Officer in Cuito at the time58. Normally, such operations were tasked with moving a combat group of about twenty-five flechas, the special PIDE native trackers, to a target area and placing them as quietly as possible four to five kilometres from their objective to minimize the possibility of alerting the enemy or of being ambushed by him. The SAAF pilots with five transport helicopters could put twenty men on the ground in a single small LZ in less than a minute. The helicopters would approach the LZ in sequence, and one by one hover two or three meters above the ground while the troops jumped from the helicopter. Once emptied, the helicopter would move ahead, thus opening a spot for the one behind it and its men. This evolution was repeated at about ten-second intervals by each helicopter, until the entire force was deposited on the ground within a minute.

During the initial deployments, the SAAF aircrews flew nearly every day with little rest and soon became exhausted. Hence, aircrew rotation was key to their efficiency. Crew replacement was at first a problem; however, the situation eased with the creation on 1 February 1968 of a second SAAF helicopter squadron, the 16th Squadron at Ysterplaat.

Beginning in September 1969, the SAAF received its first gunship at Rundu for fire support in Angola, and these now accompanied the rotations. Initially these gunships assumed a defensive posture and operated with the five troop transports carrying a Portuguese combat group. The normal routine was to have the gunship reconnoitre the LZ, and after clearing it, mark it with a smoke grenade to signal its safety. Following the sixty-second troop insertion, the gunship orbited as a counter-ambush measure to the troops now on the ground59.

As was natural, the SAAF aviators, while officially tasked with support operations, could not resist the temptation to engage the enemy alongside the Portuguese. The South Africans learned much from the Portuguese aircrews, such as locating and following enemy trails from the air. Indeed, there developed a deep mutual respect despite the language barrier. This resulted in excellent combined operations, particularly in surprise attacks on enemy encampments identified through visual reconnaissance60. The helicopter crews with their assigned paras likewise conducted follow-on search and destroy missions (batidas) immediately after an attack on an insurgent “column” to mop up the remnants.

The FAP fielded some great pilots in Wilkins’ opinion – brave characters who were completely dedicated to their cause. The one pilot who stood out in Wilkins’ memory was Alferes (2nd Lieutenant) Melo Vidal, who seemed to have an inordinate ability to locate enemy camps in the chanas that seemed to stretch from one horizon to the other. He was always ready for a scrap. In one instance at Cangamba, frustrated with the staff planners, Vidal invited Wilkins to accompany him on an armed reconnaissance mission. The reconnaissance flight consisted of two gunships plus five troop transports. In Portuguese tactics, the gunships ranged ahead of the transports, and in this case Vidal invited Wilkins to fly while he manned the 20mm cannon. Earlier Vidal had located a large camp and that day intended to reduce it with the two gunships. Once launched towards their search areas, Vidal and the other gunship took a left turn, and after about twenty minutes arrived over the camp61.

This turned out to be a large insurgent base hidden beneath a copse of trees and their foliage. Once the target was confirmed, the shooting began. Moving below 800 feet altitude to treetop level, the two gunships raked the huts and other infrastructure, until they ran out of ammunition. Shortly thereafter the transports arrived with the troops to conduct a ground sweep of the base. Documents, weapons, and prisoners were recovered. Wilkins notes that it was the most successful operation that he witnessed62. The insurgents learned their lesson and moved deeply into hiding. Further missions on that deployment were consequently inconclusive.

The South Africans teaming with the Portuguese aviators found new techniques to defeat the insurgents. For instance, the SAAF “Alos” carried Very pistols for signalling in rescue situations. The burning flare from the pistol, when fired at an insurgent wooden and thatch structure, set it ablaze, and this technique was used to reduce enemy camps to cinders63.

In another instance, it was found that high explosive (HE) rounds from the 20mm cannon would prematurely explode on contact with tree branches, falling short of their target sheltering beneath. Ball rounds, it was found, gave excellent penetration and were very effective against an enemy hiding beneath heavy foliage and forest cover. Consequently, they became a favourite of SAAF pilots, particularly as HE rounds were studiously inventoried by the SAAF authorities to make certain that they were taking only a defensive stance. Its pilots were only supposed to fire these in defence, but ball or solid rounds used for target practice were readily available64. In order to circumvent this HE restriction, there developed a barter system based on the singular weakness of Portuguese aircrews – good South African wines. Soon ample Portuguese HE rounds were available for the SAAF gunships at so many rounds per bottle of wine. Problem solved65!

From October 1969, the SAAF detachments began operating from Cangamba and Luso with Squadron 402. By the end of 1970, Portugal had twenty-four Alouette IIIs available and six Sud-Aviation SA-330 Puma medium-lift helicopters on the way for the ZML. Later, in February 1971, the Pumas began operating in the east and accelerated the response to enemy activity. Operating in pairs with a capacity of fifteen paras or commandos each and protected by one or more gunships, the formation could put thirty men on the ground anywhere in eastern Angola within five hours. This capability improved the effectiveness of envelopment operations immensely.

As air resources increased in the East, there occurred a series of annual campaigns to execute the ZML campaign strategy. The first such operation was an all-out combined FAP-SAAF effort styled Siroco 1969. This early example of air-ground coordination began in the east in September and was a counterinsurgency action which, like the hot dessert wind for which it was named, lasted the entire dry or fighting season for each of three years 1969, 1970, and 1971, and swept the endless savannas in the ZML. It also served as a vehicle for development and perfecting air assault and close air support of ground forces that would later be so devastating to the enemy. Group Siroco was formed at Luso, and its land group consisted of four companies of commandos (CCMDS), a brigade of flechas, and about 300 native auxiliary troops66. The commando teams were the centrepiece of Siroco and were expected to address enemy columns uncovered by the flechas and the auxiliaries.

The air group composition was flexible in light of the type of operation envisioned and the required transport. The limitations of the Alouette III meant that a number of trips might be made by the limited aircraft allocation to move the CCMDS. This would change with the arrival of the Pumas, but that was a year into the future. The initial Siroco air group consisted of a Dornier and four Alouette IIIs67.

The idea behind this new hunting organisation was that its elite troops were able to chase down the insurgents in the difficult countryside where they hid and to maintain contact with them by using the FAP and SAAF helicopters to move faster than their quarry. They were deposited on the ground as a group even though they may have arrived at the landing zone by a separate helicopter in the formation. Once on the ground, the assembled team went to work. The teams had the ability to call for reinforcements, if needed, and these also came by helicopter. Ultimately they were very effective in isolating and destroying any enemy formation.

The Air Group was normally limited to a three-month cycle of support because of aircraft maintenance limitations; however, maintenance requirements could be extended somewhat by reducing flight hours. This would also reduce the effectiveness of Group Siroco, as it would pose operational limits overall. The flexibility and effectiveness of Siroco, which depended heavily on air manoeuvre, was consequently reduced. On the other hand, keeping the teams together, including the aviation element, was important, as the individual members became increasingly familiar with each other’s duties and procedures and over time were moulded into a cohesive team68.

As the three-month period drew to a close, the helicopters were flown less frequently because of approaching maintenance requirements and a lack of spare parts. This declining helicopter availability affected ground mobility, and the teams became less effective, as the balance between walking and flying shifted69. The lesson here was that increased helicopter availability, or perhaps more helicopters, were needed to maintain pressure on the enemy during an extended operation. This deficit was to be corrected in later evolutions.

A new hunting group was assembled in June 1970 and began operations in July, a full two months ahead of the previous year to extend the “hunting” season – a lesson learned through the earlier experience. Its initial assignment was an area containing the Chana da Cameia, and later it was moved southward and west of Gago Coutinho to pursue the enemy along the Cuango River70. At its conclusion in October, there remained the same frustrations that had plagued operations a year earlier. Despite substantial losses in men and matériel by the insurgents, they generally understood the terrain better than the Siroco air-ground teams and thus proved highly elusive71. There were many lost opportunities because of poor radio contact between ground units and their supporting aircraft. Further, the onset of the rainy season in the midst of both Siroco 1969 and 1970 contributed to poor air-ground coordination, and it was now clear that operations needed to begin well before June to take advantage of good weather72.

A third and final Siroco was authorized in April 1971 and would operate for the three months of mid-June through mid-September along the Cuito River north of Cuito Cuanvale73. As operations progressed, the teams moved eastward toward the Zambian frontier. This sweep involved four major operations from west to east the length of the Route of the Cuando and uncovered a number of large enemy groups that were able to return fire with strength when challenged. Given the direction of the sweep, the MPLA columns moved eastward across the frontier to the safety of their Zambian bases to avoid direct confrontation74.

A month later, on 7 August, there were fifty flechas from the PIDE post at Serpa Pinto reconnoitring a group of MPLA insurgents calculated to number 200. The flechas easily located the group on the left bank of the Lunhonde River some 200 miles from the Zambian frontier along the Route of the Cuando75. This MPLA column immediately became the target of Siroco 76. The penetration of this force so far into the interior and in such numbers showed advanced MPLA capability and portended increasing support for SWAPO. At the same time in the south, large groups were attempting to penetrate similar distances from the Zambian MPLA bases of Shangombo, Kaunga, and Sinjembelle in order to bring SWAPO insurgents across southern Angola and help them infiltrate the Caprivi Strip and Ovamboland.

The MPLA had initially opened a way across the area and guided elements of SWAPO from Zambia to the region of the Cuamato people next to the Cunene River and the frontier with Ovamboland. Here, there was much cross-border sympathy among the locals, and this facilitated SWAPO border crossings. Transit of SWAPO forces supported by the MPLA thus became an increasing security problem in Cuando-Cubango and Huíla, as familiar transit routes developed across these largely empty districts where intruders were likely to be unchallenged by security forces77.

In pursuing the enemy, Siroco forces day after day “felt the guerrilla” but had little contact. The troops believed, “It was necessary to capture a live terrorist”, but no one knew when it was likely to happen, as the enemy was well led, experienced, and elusive78. The enemy truly played a “cat and mouse” game, hiding its moves in the early morning fog or cacimbo and beneath the available foliage79. Lieutenant Colonel Ramires de Oliveira recorded, “That very evening we captured a prisoner, and he confirmed that the enemy columns had passed through our area” and across the Zambian frontier80. While the enemy had felt the pressure of combined operations, he largely lived to fight another day.

The follow-on to the Siroco series was the formation of Group Raio, thunderbolt, which like its name shocked the MPLA columns. It was formed and deployed in June 1972, and its operations ran for the three months from July to October. It was the largest such operation in the east yet with a ground force of three CCMDS, two companies of infantry, one of cavalry, six of auxiliary troops, and six groups of flechas 81. Raio was tasked with sweeping clean two primary enemy routes from Zambia into Angola: Route of Agostinho Neto (Luena River), and Route of the Lungué-Bungo. The results were impressive by any standard. Several major columns were destroyed, and the MPLA suffered 121 deaths, with many more wounded, and 138 captured82. This broke the back of the MPLA and reduced the SWAPO threat from Angola.

Group Raio operations were extended into Cuango Cubango in January 1973 to neutralize MPLA squadrons “Big Man” and “Sandalo”. The ground force remained of similar size; however, it was augmented by five FAP Alouette IIIs and seven SAAF Alouette IIIs, all coordinated through the CCAA/JASC at Cuito Cuanavale83. The entire force was organised into ten hunting groups, and was aimed at the area bounded by Gago Coutinho, Muié, Chiume, and the frontier with Zambia84. It intended to sweep the zone of MPLA columns and eliminate the MPLA encampment “Capoche”, which was next to the Luate River and about ten miles into Angola from the Zambian frontier85. It was believed that “Capoche” held about thirty insurgents86. The ground force contained two CCMDS and about 1,200 auxiliary troops87. The air group was a combined FAP-SAAF force with the following aircraft:

– Period 29 September-7 October:

• 1 Alouette III gunship (FAP);

• 5 Alouette III troop transports (FAP).

– Period 7-17 October additions:

• 1 Alouette III gunship (FAP);

• 1 Alouette III gunship (SAAF);

• 5 Alouette III troop transports (SAAF);

• 1 T-6G Harvard (FAP – based at Ninda);

• 1 Dornier DO-27 (FAP – based at DC “G”);

• 1 Cessna 185 (SAAF).

As operations progressed, Group Raio identified a number of heavily armed enemy columns in encampments scattered through the targeted area, and these columns were capable of sustained resistance, that is, fighting for between one and two hours88. At the onset of an engagement, the insurgents would then abandon their camps and retreat under covering fire across the border into Zambia. The abandoned camps contained substantial numbers of weapons and munitions, all of which could be readily replaced by the enemy from obsolete communist bloc stockpiles89.

Group Raio was concluded on 17 October, and from then onward MPLA activity was confined to the border. Insurgent forces within the ZML had been destroyed, and the fighters, unlike their weapons, could not easily be replaced. For the UPA/FNLA the crisis was complete. For the MPLA, it was reduced to sneaking across the border and planting mines along the frontier roads. Its actions were violent and short in both duration and penetration. For SWAPO, it was no longer able to use Angola for access to SWA.

In the East there developed a perfect resonance between the FAP and SAAF helicopter pilots and the Portuguese ground forces, particularly the elite forces termed intervention troops. The FAP-SAAF logistics of supplying aviation and ground support was strengthened to the point that operations against insurgent columns in the ZML were extended from the normal three or four days to twenty-two days90. This extension put enormous pressure on the insurgents and increasingly isolated them far from home – a situation that took a heavy toll. Lastly, the melding of intelligence with the activities of the air-ground force team enabled the very effective pursuit and destruction of the enemy columns. The assiduous practice of this concept through the Siroco and Raio series of seasonal campaigns produced air-ground tactical teams of devastating capability in a difficult physical environment. In an appraisal of the situation, Brigadier Hélio Felgas, commander of the ZML, reported that, by the beginning of April 1974, there was no contact between Portuguese forces and the insurgent groups of any of the nationalist organisations. By the end of April the southeast of Angola was calm, and insurgent activity was practically non-existent91. It was indeed a sweet taste of victory for the combined FAP-SAAF effort.

South Africa and Portugal found common cause in combining their resources and capabilities to defeat multiple threats to their national territories despite their cultural and linguistic differences. The South Africans, with their Dutch and British heritage, were able to work effectively with the Portuguese from the strategic to the tactical level in apportioning resources and responsibilities. The South Africans filled a matériel gap, particularly in eastern Angola, with manned helicopters, fuel, spare parts, and airfield accessories, while the Portuguese contributed manpower in the form of commandos, paras, and native auxiliaries, as well as construction labour and material to build the needed airfields. The joint project lasted from 1966 to 1974, some eight years, and both parties took the long view in forming a strategy to defeat their enemies, in planning tactical operations that led to strategic success, and in developing an extraordinary combined FAP-SAAF air-ground team that adjusted effectively to its contrasting composition. Impressively, all of this was achieved in the remote reaches of eastern Angola – some of the most forbidding and difficult terrain in which to fight an insurgency. The logistics alone needed to put the proper forces where they were effective was a herculean effort in itself. Overall the campaign was conducted with the utmost discretion, and even today many details of it remain obscure. Yet, it stands as a classic example of a successful counterinsurgency campaign in which two unlikely allies teamed to reduce a common threat.

Map 1. Eastern Military Zone, 1968-1974.

Map 2. Airfields in Angola, 1968-1974.

________________________________________________________

* Membro Associado da Academia de Marinha, da Classe de História Marítima, investigador e Membro-adjunto do Instituto de Análise da Defesa, Scholar in Residence na Universidade de Virgínia-EUA e Professor aposentado da Marine Corps University. Doutorou-se em 1996 no King’s College, Londres. É Capitão-de-mar-e-guerra aposentado e piloto-naval especializado em aviação de reconhecimento marítimo. Desempenhou diferentes funções, inclusive de comando, na Força Aérea da US Navy e serviu no Gabinete do Chefe do Estado-Maior da Armada e no Gabinete da Secretaria da Defesa. Em 2005 publicou a obra Contra-Subversão em África (Prefácio), e em 2009 a obra A Marinha em África (Academia de Marinha) e, em preparação para publicação, a obra Plano de Voo África (Comissão Histórico-Cultural da Força Aérea).

** Licenciado em Química pela Universidade de Lisboa e professor do Quadro do Ministério da Educação. Dedicou as duas últimas décadas à pesquisa da história da Aviação Militar lusa em arquivos militares e diplomáticos nacionais e estrangeiros. Publicou mais de setenta artigos relacionados com a II Guerra Mundial, as operações Aliadas nos Açores, a criação da Força Aérea como ramo independente das Forças Armadas, nos anos 50 do século XX, e a guerra aérea nas antigas províncias ultramarinas entre 1961 e 1974. Investigador e membro da Comissão Histórico-Cultural da Força Aérea Portuguesa. Agraciado com a “Medalha de Mérito Aeronáutico de 2ª Classe”.

1 Aniceto Afonso and Carlos de Matos Gomes, ALCORA: O Acordo Secreto do Colonilaismo, 73.

2 Ibid.

3 John A. Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, Vol. I, The Anatomy of an Explosion (1950-1962), 347-351. Marcum lists some fifty-nine groups affecting Angola alone beginning in the 1940s and either merging with one another or vanishing by 1962.

4 Malyn Newitt, Portugal in Africa: The Last Hundred Years, 190.

5 Douglas L. Wheeler and René Pélissier, Angola, 167. The authors cite as an example the Congo district in 1960. For its 37,000 square miles it had fourteen concelhos (basic urban or semi-urban administrative unit) or circunscrições (basic rural administrative division) and thirty-seven posts, for an average of 725 square miles per administrative division. This presence would hardly be effective in controlling a frontier, as the posts would be dozens of miles apart. Large numbers of people could and did cross undetected.

6 Shola Adenekan, “Holden Roberto”, The New Black Magazine (22 October 2007): http://www.thenewblackmagazine.com/view.aspx?index=1042 (accessed 5 January 2017).

7 Willem van der Waals, Portugal’s War in Angola,1961–1974, 96.

8 Charles A. Fraser, Operational Briefing Notes: Part One – The Situation in South East Angola Provinces of Moxico and Cuando Cubango as at 14 NOV 1969, Headquarters, Joint Combat Forces, Voortrekkerhoogte Military Base, Pretoria, 18 November 1969, South Africa National Document Centre-Department of Defence Archives, 1969 (Top Secret – declassified), 4.

9 António Lopes Pires Nunes, Angola 1966-74, Vitória Militar no Leste, 40.

10Ibid.

11Comissão para o Estudo das Campanhas de África, Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África 1961-1974, 6 Volume, Aspectos da Actividade Operacional, Tomo I, Angola-Livro 2, 353.

12Ibid.

13Willem Steenkamp, South Africa’s Border War, 1966-1989, 18.

14Ibid.

15Ibid.

16Ibid.

17Ibid., 22.

18Pires Nunes, Angola 1966–74, Vitória Militar no Leste, 10.

19António Lopes Pires Nunes, Siroco: Os Comandos no Leste de Angola, 45.

20Ibid., 42.

21Note 268/67 from the Comando-Chefe das Forças Armadas em Angola-Luanda to Secretariado Geral de Defesa Nacional-Lisbon (28JAN1967). Portuguese Air Force Historical Archive (AHFA) via general Costa Santos

22Dispatch from the Minister of National Defence, 2 March 1967. National Defence Archives, Minister Cabinet Documents1967 (Paço de Arcos).

23Proceedings of the 2nd Air Region Command Meetings. Luanda, September 1967, AHFA.

24Ibid., March 1968.

25Eduardo Koll de Carvalho, “As Infra-Estruturas Aeronáuticas em África: Antecedentes e Implantação das Delegações em África”, 29–31.

28António Silva Cardoso, Angola, Anatomia de uma Tragédia [Angola, Anatomy of a Tragedy] (Lisbon: Oficina do Livro, 2000), 297.

29Pires Nunes, Angola, 1966-74, 28-30.

30John P. Cann, Flight Plan Africa, 364.

31Paulo Correia and Grietjie Verhoef, “Portugal and South Africa”, 62.

32José Augusto Queiroga, “Histórias Vividas: Por Terras do Fim do Mundo, Uma viagem entre os 18 e os 9 graus de Latitude Sul” [Tales Lived: For the Lands at the End of the Earth, A trip between 18 and 9 degrees South Latitude], page 4, undated deposition, Caixa 181, Archivo Histórico de Força Aérea, Alfragide; and Mário Diniz and Luís Proença, “AL III, História Breve de uma Vida Longa, 1963-2013”: 24-25.

33Ibid., and John P. Cann, Flight Plan Africa, 382.

34Peter Wilkins, Chopper Pilot (Nelspruit, South Africa: Freeworld Publications, 2000), Chapter 2, Angola Operations.

35Ibid.

36Annual Command Report, 2nd Air Region-1968, PAFHQ-Luanda. AHFA.

37Helmoed-Römer Heitman and Paul Hannon, Modern African Wars 3: South-West Africa, 14.

38Victor Swanepoel, SAAF pilot, private communication to the author, April 2002.

39Ibid.

40Força Aérea no Leste de Angola, Comando Aéreo Leste, Luso, 30 November 1972, Directiva 2/72, Annex A, AHFA, 355, A3, Y3.

41José Augusto Queiroga, “Histórias Vividas: Por Terras do Fim do Mundo, Uma viagem entre os 18 e os 9 graus de Latitude Sul,” 5-7.

42Força Aérea no Leste de Angola, Comando Aéreo Leste, Luso, 30 November 1972, Directiva 2/72, Annex A, AHFA, 355, A3, Y3.

43Peter Wilkins, interview by Al J. Venter in Portugal’s Guerrilla Wars in Africa (Solihull: Helion & Co., 2013), 448.

44Paulo Correia and Grietjie Verhoef, “Portugal and South Africa”, 62–63.

45Charles A. Fraser, Operational Briefing Notes – Part 2: Reasons for Deterioration of Portuguese Control in East and South Eastern Angola, Headquarters, Joint Combat Forces, Voortrekkerhoogte Military Base, Pretoria, 18 November 1969, South Africa National Document Centre – Department of Defence Archives, 1969 (Top Secret – declassified), 11.

46Ibid., 7.

47Annual Command Report, 2nd Air Region-1969, AFHQ-Luanda. AHFA.

48Al J. Venter, Portugal’s Guerrilla Wars in Africa, 448.

49Norma de Execução Permanente, NEP 1-1969, 2nd Air Region Command, AFHQ-Luanda, 10 January 1969. AHFA.

50Ibid.

51Ibid.

52Carlos Alberto Melo Vidal, FAP helicopter pilot, interview by the author, Lisbon, 2002.

53Norma de Execução Permanente, NEP 1-1969, 2nd Air Region Command, AFHQ-Luanda, 10 January 1969.

54Ibid.

55Ibid.

56Simon “Sej” Dunning, SAAF helicopter pilot, correspondence with the author, April 2002.

57Al J. Venter, Portugal’s Guerrilla Wars in Africa, 446.

58Dunning correspondence, April 2002.

59Ibid.

60Ibid.

61Al J. Venter, Portugal’s Guerrilla Wars in Africa, 450.

62Ibid.

63Ibid, 445.

64Ibid.

65Ibid., 444.

66Pires Nunes, Siroco, 160-161.

67Ibid., 163.

68Ibid.

69Ibid., 195.

70Ibid., 295.

71Ibid., 332.

72Ibid.

73Ibid., 407-408.

74Ibid., 503.

75Direcção Geral de Segurança, Acções das Nossas Forces [Actions of Our Forces], DGS-Angola, 11 August 1971, SDGN 1802, Intelligence Report 947, Arquivo da Defesa Nacional, Paço do Arcos, Portugal.

76António Pires Nunes, Siroco: Os Comandos no Leste de Angola [Siroco: The Commandos in the East of Angola] (Lisbon: Associação de Comandos, 2013), 364-422.

77Direcção Geral de Segurança, Luanda, Angola, Cuanhamas–Political Subversion Situation], Intelligence Report 37/72-DINF-2a, 8 July 1972, document F1.07.37.64, Arquivo da Defesa Nacional, Paço do Arcos, Portugal.

78Ibid., 505.

79Ibid.

80Ibid.

81Ibid., 506.

84Comissão para o Estudo das Campanhas de África, Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África 1961-1974, 6 Volume, Aspectos da Actividade Operacional, Tomo I, Angola – Livro 2, 373-376.

85Pires Nunes, Siroco, 598.

86Ibid., 597.

87Ibid., 599.

88Ibid., 601.

89Ibid., 601-603.

90Corbal, Simões, Ferreira, and Almendra, 24.

91Hélio Felgas, “Opinião” [Opinion], as quoted in Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África, 1961–1974, 6th Volume, Tome I, Book 2, Angola by Comissião para o Estudo das Campanhas de África (1961–1974) (Lisbon: Estado-Maior do Exército, 2006), 450.

Licenciado em Química pela Universidade de Lisboa e professor do Quadro do Ministério da Educação. Dedicou as duas últimas décadas à pesquisa da história da Aviação Militar lusa em arquivos militares e diplomáticos nacionais e estrangeiros. Publicou mais de setenta artigos relacionados com a II Guerra Mundial, as operações Aliadas nos Açores, a criação da Força Aérea como ramo independente das Forças Armadas, nos anos 50 do século XX, e a guerra aérea nas antigas províncias ultramarinas entre 1961 e 1974. Investigador e membro da Comissão Histórico-Cultural da Força Aérea Portuguesa. Agraciado com a “Medalha de Mérito Aeronáutico de 2ª Classe”.