Nº 2632 - Maio de 2021

Pessoa coletiva com estatuto de utilidade pública

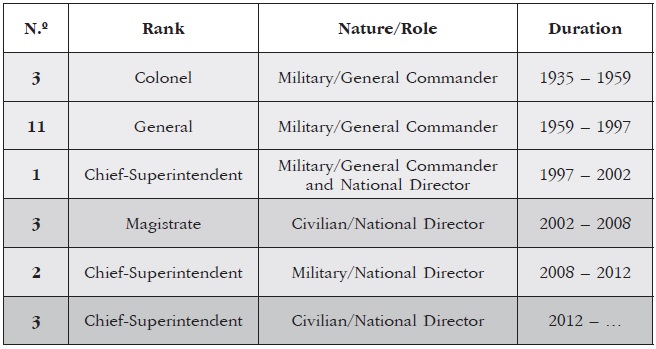

The History of the Police in Portugal is bolstered by the History of military leadership, as Army officers have left an indelible mark, with a lasting impact in its organisational culture. This is still very much visible in the practices and rituals of the professionals who exercise command in the Polícia de Segurança Pública (PSP), which in turn, has contributed to an identity crisis that remains latent[1] in the socio-professional configuration of its administrative elite. The PSP was led by commanding generals (until 1999) and national directors (until 2002) from various Army Forces on a service commission. From 2002 to 2008, the Police were directed by national directors assigned to the judiciary and the Public Ministry[2]; in the period from 2008 to 2012 the national directors from the Army took over and integrated in the PSP cadres[3]; subsequently from 2012 to the present, the first national directors[4] trained by the Superior School of Police (current Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Homeland Security) followed.

In the early days of Portuguese democracy, marked by the 25th April 1974 revolution, the Armed Forces Movement Program (MFA) determined as an immediate measure, the reorganisation and regeneration of the all armed, militarised and police forces in Portugal. Along this path, a process of reconfiguration of the Police was initiated, with the consolidation of a security force with a civil matrix grounded on the respect for the rights, freedom and guarantees of citizens. This would be firstly achieved with the development of a higher education police establishment for the training of future administrative elites, whereby the cycle of leadership from the military schools[5] could be interrupted.

This article aims to understand the relationship between the military and police universes, particularly in the PSP, a security force with a civilian matrix, but based on principles inherited from a military culture. In order to achieve this, it is crucial to highlight the creation of the Escola Superior de Polícia in 1982[6]; the designation and curriculum of the Police officers training course[7], the 1999 Organic Law, which strengthened its civilian matrix[8]; and rituals, categories, symbols, careers, graduations, parades, salutes and police honours. To accomplish this purpose we intend, with the contribution of a socio-historical appreciation, to answer the following question: what was the contribution of the military leadership to the consolidation of police administrative elites in Portugal? As specific objectives, we consequently delineated the following topics: understanding what it means to be a leader in the current Portuguese Police; identify the military-inspired characteristics of the Portuguese police; and comprehend if the leadership in the Police is distinguished from the action taken by a military leader.

The notion of “elite” usually refers to a restricted group of individuals considered, within a certain group or class, as the most gifted, the best and/or the most important, distinguished by the possession of certain characteristics that elevate them over the others. In this sense, authors such as Michels (1914), Mosca (1953) and Pareto (1968) among others, emerge as pioneering theorists[9], and argue that “[…] elites are the most powerful 3-5 per cent of people within any national political system. They are the people who make or shape the main political and economic decisions: ministers and legislators; owners and controllers of TV and radio stations and major business enterprises and activities; large property owners; upper-level public servants; senior members of the armed forces, police and intelligence services; editors of major newspapers; publicly prominent intellectuals, lawyers and doctors; influential socialites and heads of large trades unions, religious establishments and movements, universities and development NGOs[10]”.

Finally, Pareto defined “elite” as the group of the best in each area of activity and divided the elites into government and non-government. In turn, Mills (1999) proposed a more empirical view, showing that the post-World War II American elites emerged from three groups: the occupants of the most notorious political posts; the owners and managers of the largest economic groups; and high military ranks. More recently, Hossain and Moore (2009) defined “elites” as the people who shape and make major economic and political decisions, including senior civil servants, senior military, police and secret service leaders, as well as influential social personalities[11]. The power elite is thus, made up of individuals whose position has allowed them to transcend the common social environment[12].

In the light of this vision, the Portuguese elites integrate people who occupy decision-making positions in the economic, political, media, military, academic, scientific, cultural[13] and police spheres, taking into account the socio-professional consolidation of the superior officers from the Superior Police School since 1984 and the Portuguese police process or civic matrix. However, the investigation of administrative elites in the democratic period is still scarce[14], particularly studies directly concerning the Police[15] forces, a reality that we intend to revise with the present study.

The beginning of the 21st century imposed new challenges and approaches to the concept of “leadership”. Currently, the dynamics of organisations[16] are widely debated, the management of change curves, the cultivation of relevant leadership[17], teamwork[18]; rhetoric, influence and moral, social and emotional intelligence[19]; positivity and high performance; the virtues of design thinking; networking and social networks in professional environments; bench learning; the learning organisation, continuous improvement and total quality[20]; social responsibility and business ethics[21]; leadership by example[22]; the importance of knowing how to demand in an assertive, polite and pedagogical way; delegation[23], accountability and management by objectives; the management of motivations[24], the creation of environments of enthusiasm and values[25] and “360º leadership”. According to Maxwell[26], a leader is someone who has a communication capacity and is able to lead in all directions, a “360º leader”, influencing people at all levels of the organization[27]. The recognition of an element as a leader does not come from his position in the field and his resources, but from the recognition of others in his ability to guide them. This capacity is transformed into the innate quality of a leader, a “state of grace” that can vary for a long time[28].

But are these concepts new? Or do they represent the same approaches adapted to the current context? In 1978, MacGregor Burns introduced the concepts of “inspirational motivation” and “transformational leadership”[29]; and since the mid-20th century, it has been argued that leaders must learn to develop a social architecture that encourages brilliant people to work as a team and to strengthen their creativity, as the biggest challenge facing leaders will be the ability to free the “Gray matter” present in their organisations[30] and the management of motivations[31]; conjugate theories of motivation with an emphasis on objectives, focusing on the processes of self-regulation and the role of affections[32], with an increasingly necessary understanding of technological dynamics for managers[33].

However, there are principles that must remain unchanged, despite the new reality. In order to be able to lead people in an inspiring way, regardless of their social, historical and technological situation, ethical values must remain; which means that we find identical principles in the military, police or business world. We recall a famous Exhortation[34], by Charles Fouquet (1684-1761), Duke of Belle-Isle and Marshal of France, one of the fundamental figures in the Military History of Europe in the 18th century, who would influence Napoleon Bonaparte and Carl von Clausewitz, and would later have a major impact on the Portuguese military theory and thought. Marshal de Belle-Isle is the author of the Exhortation, an epistle addressed to his son, written shortly after being appointed colonel of a regiment. There he urged respect for the guiding principles of a commander: respecting the second commander, humility, knowing how to listen to the oldest, making oneself loved by his men while being disciplined, avoiding offensive words; punish justly; be a scholar; in short, the balance between the ability to supervise and correct behaviours and the capacity to be an inspirational guide whilst leading by example, a premise that is always applicable in current leadership, as we defend.

The military define leadership as a process of influencing, beyond what would be possible through the exclusive use of invested authority, and the human behaviour intended to fulfilling the purposes, goals and objectives established by the current organisational leader[35]. The term “leadership”[36], both because of the influence of NATO’s military doctrines (mainly with American influences), and because of what happens in the business and political spheres, impelled our Armed Forces, to gradually replace its term “chieftain”.

The military in a command function will only be an effective leader, when he manages to influence the behaviour of his subordinates towards the fulfilment of the mission and becomes an example according to law and ethics[37]. The power of this referenced behaviour when translated and exercised into a legitimate act, can make all other facets of Power redundant and transform an “impure leader” into a “pure leader”[38]. Subsequently, an “impure leader” is usually a designated organisational leader, who holds formal power even before the opportunity to become leader, hence the sense of ‘impurity’ which derives from an invested legal mandate to exercise power. Thus, we are in the presence of the legitimation of power and authority, through rational legal means. Such is the case of administration presidents, unit commanders, professors and other actors, showing that holding power in an organisational context is more of an attribute than a question of individual ownership[39].

A Police force is the most visible symbol of our formal control systems, the most present in the daily lives of citizens and also, the first-line enforcer of criminal law[40]. Police officers are above all, knowledge workers and information mediators[41], an increasingly demanding activity, which requires a more holistic investment in training in order to ensure that a police officer is continuously equipped with all the necessary tools to handle today’s society rising challenges[42]. Following this line of thought a few questions arise: is there a police leadership? Does the mission of a civilian police force, with the characteristics of the PSP, require a command action distinct from military leadership? Or are there different leaders depending on the organizational culture, including among the forces and security services?

Recent international studies[43] demonstrate that, when an analytical approach to the practice of police leadership is developed, as an alternative to normative management models – which generally focus on characteristics and

how police leaders should lead –, the importance of structural, cultural and contextual undercurrents, as well as the emerging nature of leadership practices, will revolve around four distinct dynamics: production, relationship, interpretation and negotiation. These dynamics reveal concerns about the relationship between the leader(s) and the ones being led, usually characterized by the ideas of “taking care of each other” and “us against each other”, along with the development of a common language, the use of symbols, the sense of mission and a strong sense of belonging.

In the course of its activity, a Police force will always have to manage the dichotomy between the sovereignty of the State from which it depends, whilst constantly also looking down at the the society in which it immerses[44], and from where public opinion[45] arises. In other words, many leadership decisions are permeable to political decisions and social representations. On the other hand, the cooperative spirit of the police is exacerbated and a responsibility for failures develops. The policemen reveal a feeling of abandonment and without means in the face of difficulties in the field of action, making general failures, errors and demotivation plausible[46]. In addition, in the case of the PSP, there is a feeling of growing doubt about the leadership model to follow: a return to the military model? Or the Judiciary Police paradigm, which is identical in terms of direction and leadership to Public Administration? What should be the model, considering that they are institutions with different organisational cultures[47] and even different historical paths[48]?

The PSP is a hybrid of the military and bureaucratic model and therefore, reveals difficulties in defining itself. But most policemen understand that police rituals must be maintained or established, some of which are of military heritage; like rewards, praises and prizes[49]. Dias (2012) argues that we are experiencing an organic and functional crisis in the police. In parallel with the loss of the monopoly of the administrative security function, based on a restructuring of security governance with the emergence of new actors; and the transition from an administrative-bureaucratic functioning model to an administrative-business model. In addition, administrative security function processes require evermore scientific knowledge and better management while working in close connection with civil society, which in turn, reinforces its legitimacy and regulation[50]. The PSP has however, developed several procedures which may violate the jurisdictional sphere of other actors[51], due to the inability of some sectors to meet all the needs of certain risk groups, reinforcing thereby the role of the police.

When the first ISCPSI cadets began to be trained, soon became apparent that all the signs of deference and respect that, as a rule, a large part of the agents and chiefs had in relation to the army and police officers, was still very much present. However, part of these future officers forgot that these signals and behaviours should be continuously stimulated, otherwise they would risk fall into disrepair. Associated with these factors, the idea that the exercise of command is a very solitary act, even if it implies knowing how to listen, has never been truly assimilated, but rather imposes a distance and the preservation of a certain image.

Now, that is not what has happened. As a result of some inexperience and in order to facilitate the fulfilment of the diverse objectives that emerged then, many officers felt the need to approach the bases excessively, distorting the role of each of the protagonists and the limits that should exist between people in a force security and police duties. People started to speak at the same level and the deference’s behaviours began to fade. Some officers stopped demanding deference’s, ignoring the fact that this behaviour is part of the organisational culture, and refers to a category within the force and not to a particular individual. Currently, there is a relaxation of the codes and signs that have always characterised the Portuguese Police. In the face of an evident identity crisis, the hiatus is growing among those who want to separate themselves from military rituals, and those opposing this status quo by wanting to keep a tradition and culture of military inspiration.

Therefore, it is important to rethink leadership training, and to reinforce the consolidation of values, respect for hierarchy and discipline. The maintenance of these behaviours becomes the first argument for not distinguishing the legitimacy associated with a police officer as a “pure leader”. In addition, the PSP National Directorate must embody values, discipline and pride in the uniform and serve as an example for all policemen, while personifying the nature of police leadership, that is, upkeeping some rules of military inspiration for the purposes of command, in parallel with a more moderate posture in human relations and centred on the rights, freedoms and guarantees of citizens.

In fact, the police mission is not identical to the military mission, although the line that separates internal security from national defence is progressively blurred, as there are no more foreign affairs forces in Portugal, but only an internal security policy: this is the Police force’s domain and not the Armed Forces’[52]. What is intended is that personnel develop a mandate committed to the objectives of the institution. This implies loyalty, selflessness and a sense of duty. In the police, this desire is fundamental. Ordinary citizens are not concerned with internal disputes, wages, unions’ claims, the lack of resources or the academic training of police officers. Their concern is only one: mass crime, that is, knowing that their legal assets (and those he loves most) are safeguarded, that their residence is not burglarised, that their vehicles are not stolen; that their children are not victims of wrongdoing and, in the event that they do, that there is a police force capable of combating these violations. For this to happen, security forces must develop their mandate diligently and professionally, which requires them to be motivated to guarantee operational levels of response, which can be rendered by a proactive, cohesive, and visible police force responsible for ensuring public safety, as expected. Police officers must feel that the institution is the first one to be concerned with its internal public, because only with satisfied personnel can we provide to our “customers”.

This challenge means that police leaders must develop a mandate, in the light of immutable and transmissible principles, right from the start of initial training, where the CFOP – Training Course for Police Officers –, is particularly relevant, given at ISCPSI, with a duration of five academic years. This length of time is considered essential to form a future police commander with scientific knowledge, based on the intra and interdisciplinary dialogue of the Police, Human and Social Legal Sciences to face the security problems of society and global risk issues.

In this context, it is important to highlight the leadership in the feminine, an aspect considered crucial in modern management, including in the security forces, where women have acquired a growing protoorganism at the top of the hierarchy[53]. The first female police officer enlisted in the PSP took place on November 1, 1930 and, throughout the 1940-1950s, women were admitted to the service of the Institution[54]. However, the number of women on duty at the police still does not correspond to the real needs, right from the outset in assisting female victims for example, particularly in crimes of sexual and domestic violence[55].

In this section, it is important to examine how military leadership[56] contributed to the socio-professional reconfiguration of the administrative elites of the Portuguese Police. To that end, we must clarify the concepts of “identity” and “social representation”. Currently, sociological research on professional groups has developed by incorporating the dimension of identities and the empirical extension to categories with sensitive public visibility (military, police[57], etc.)[58]. Social representations are configured by the conjuncture, from which they emerge through an attribution of meaning to that same context[59]. Blin (1997) defined professional representations as social representations elaborated in professional action and communication, specified by the contexts, the actors belonging to groups and by the objects relevant to the exercise of professional activities[60]. On the other hand, identity is associated with professional, theoretical, practical or technical information, and the knowledge of an organisation[61].

It was necessary to arrive in the second half of the 19th century in order to witness the industrial undertakings of António Maria de Fontes Pereira de Melo[62], Minister of the Kingdom, and observe the complete modernisation of Portuguese society: we were, then, at the very start of Regeneration[63] period, which extends until the English Ultimatum[64] (11th January 1890) and the first republican movements[65] (31st January 1891). By direct intervention of D. Luís[66], o Popular, the Civil Police[67] (2nd July 1867) was created, progressively adapted to an urban reality – not forgetting on the other hand, the decisive role of Civil Governments –, articulated in a security network extending to the entire country, in a continental, insular and overseas logic, allied to the African colonialist effort[68].

On this occasion, the day before Civil Police’s creation (1st July1867), which would not be the result of a random event, Portugal became the first country in Europe to abolish the death penalty[69] for civil crimes (although only formally extinguished for military crimes after the promulgation of the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic, on 25th April 1976). In that same year, as a result of countless civic/civil solicitations, the first Civil Code with a patently Napoleonic matrix and authored by António Luís de Seabra[70] (1798-1895), 1st Viscount of Seabra, would also be published and would remain in force until 1967, finally determining the end for the legal authority of the Ordenações Filipinas, which was still being used as a legal reference in Portugal since the 17th century (1603).

With the introduction of the Civil Police in the national internal security panorama, mainly through the leadership of Commissioner-General Colonel D. Diogo de Sousa[71] at the heart of the structural reforms of this force (1892, 1896, 1898), the designation “Polícia de Segurança Pública”[72] first appeared, although considered initially as an operational division of the Polícia Civil. In the period between the establishment of the Republic and the advent of the military movement in May 1926, there would be a further change in the name of this police force for “Polícia Cívica”[73], a fact that still clouds historians themselves today. In this paradigm is crucial to remark the leadership of a real man of war, Colonel João Maria Ferreira do Amaral[74] (1876-1931), general commissioner of the Civic Police, whose personal influence was essential for the creation of a modern police force’s ethos.

After the military coup of on the 28th May 1926, the Military Dictatorship period followed, until the rise of the Estado Novo and the promulgation of the Corporate Constitution (1930-1933). These political momentous considerably altered the civic police model, particularly in the periods between 1933 and the end of World War II, in 1945. The Decree No. 25338, of 16th May 1935, would extinguish the General Directorate of Public Security and create the PSP General Command, whose commander-general will accumulate functions with the command for the Lisbon PSP. In 1953 the PSP Statute was published and would be in force until 1985. This issue would reorganise the PSP as a militarized body, dependent on the Ministry of the Interior. As for the top of the hierarchy, this diploma established that the position of commander-in-chief would be held by an officer of any Army Corps, active or in reserve, with a rank not lower than of a colonel[75].

Accordingly, the strategic lines of the PSP would be repositioned and aligned with a militarised concept, a type of ‘second line’ troops, which emphasised the tenacious hierarchical obedience to the military institutions and the political police of the regime, initially under the designation of PVDE – Vigilance Police and Defense of the State[76] (1933-1945) or later, in a subsequent conformity of the Cold War, the PIDE[77] – International State Defense Police (1945-1969) followed later on, in the course of the Primavera Marcelista [78], by DGS – General Directorate Security (1969-1974).

Soon after the revolution of 25th April 1974, the police and militarized forces[79] would go through an arduous period, mainly due to the institutional unclarity which derived from the force’s connection to the deposed political regime. This status was particularly unclear during PREC[80] – Revolutionary Period in Progress (1974-1976), since the police force was still considered to be a subordinate to the Armed Forces. Looking for a new functional balance (1976-1983) and supported by the consolidation of the democratic regime in Portugal, the PSP gradually adopted a new police paradigm (1985-1999), to which the 1985, 1994 and 1995 reforms were not alien.

Following this dynamic, in 1982 the Escola Superior de Polícia[81] was created and in 1985, the commander-general and the 2nd commander-general of the PSP started to be appointed among the general officers in the ranks of general and brigadier, respectively[82]; or Police officers of a rank not lower than superintendent with a minimum of 4 years in the same rank. From this moment on, and for the first time, the opportunity arose for the post of commander-in-chief to be held by a police officer. Consequently, Army officers, placed in the PSP, were given the possibility to return to the original units or transition into the PSP career. In 1994, the new Organic Law of the PSP[83] came to define that the commander general would be chosen from among Army officers with the rank of general or from among Police officers with the category of chief superintendent.

In 1996, the Organic Law of the PSP was amended[84], determining that the commander-general, in addition to a general or chief superintendent, could also be a magistrate or other person of recognized repute. In 1999, the police nomenclature was changed, creating the figure of the national director, replacing the commander-general, and recruitment started to be reserved for chief superintendents or individuals with an academic degree and, of recognized reputation and professional experience[85]. From 1935 to the present, the PSP registered 23 commander-generals (from 17th May 1935 to 29th March 1999) and national directors (since 30th March 1999). From these, 17 would come from Army ranks, 3 from the judiciary and 3 others from within the ranks of the police career trained at the Police Superior School (current ISCPSI). As follows (figure 1):

Figure 1 – Police General-Commanders and National Directors.

The need to establish a body of officers with specific training to command the PSP, gradually replacing Army officers, was in 1979, one of the main motives supporting the creation of a police higher education school, materialized in the publication of Decree-Law No. 423/82, of October 15th, which effectively created the Superior Police School. In February 1999, ESP began to be designated as the Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security (ISCPSI), in accordance with Law No. 5/99, of 27th January, taking on new missions in police higher education paradigm[86].

History shows that the PSP has an umbilical connection with the Army, which for some authors, poses a problem. In the line of thought of Silva (2017), the PSP is based on bureaucratic and rigid system, similar to its military counterpart the National Republican Guard, which makes it difficult to adapt to social changes[87]. The regulation of police salutes and honours[88] in force shows several signs of military inspiration: the duties of saluting and deferring to superiors; entry into a police vehicle that begins in ascending order of category or function, leaving in reverse order; the model and concept of police ceremonies (e.g. parade forces search, honour escort, etc.), etc.

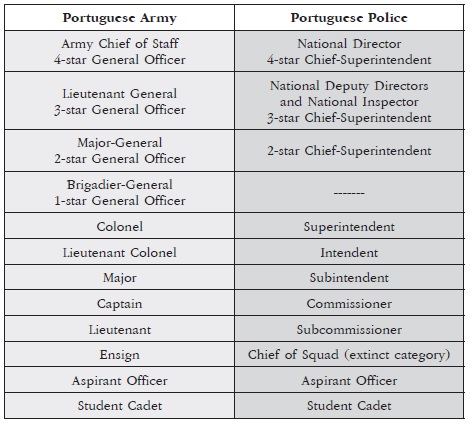

In addition, in PSP there are three careers (officers, chiefs and agents) similar to the Army (officers, sergeants and soldiers), with a strong similarity in the symbology used, in particular by officers, and a tendency for the Ministry of Internal Administration (in appointment to missions and/or in protocol at ceremonies) to equate, for example, a commissioner with a captain or a superintendent with a colonel. If not, let’s see (figure 2):

Figure 2 – Officer career (Army vs. Police).

Despite the fact that general police missions should not to be confused with military assignments, there is evidence of a concerted effort by the Army to obtain a greater role in internal security affairs, similar to the military experiences and exercise of police functions in Brazil[89] and France[90], among other countries. On 18th July 2018, the L’Engagement des Forces Armées sur le Territoire National: l’Expérience Française conference was held, with the French Army Chief of Staff as speaker, at the invitation of the Portuguese Chief of Staff, at the Military Academy. This was yet another action to strengthen the military’s position on its role in internal security and an effort to mitigate the loss of its symbolic value in peacetime.

The difficulties in the dialogue between the Police and the Army are evident, as an episode in 2020 demonstrates, following the police identification of armed military personnel called to establish a security perimeter in a nursing home, that was being decontaminated in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic[91]. This incident had a significant projection in the media, and again underlined the difficult institutional relations between forces, which in the Portuguese case, have abundant common characteristics, as concluded from the historical analysis.

In view of the current security problematics, discussing the composition of elites and their leadership functionality, may contest the current organisational thinking, whereby the role of the individual is by itself, excessively exacerbated, particularly when examining group dynamics. These will always be sensitive themes, often due to their historical past and previous institutional ties. The subject could even become more delicate when referring to the military forces, militarized or police institutions, sometimes regarded with a certain disdain by other scientists and social analysts[92].

It is imperative to reflect on elites and leadership, seeing their historical role and focusing specifically on their current situation, without forgetting future guidelines in the face of organisational reform. Ultimately, it is important to reinforce the hierarchical authority of these organisations, which is sometimes undermined internally and externally by numerous factors, favouring, in turn, the strengthening of the central apparatus of the State. And with regard to such organisations and hierarchies, oscillating between the civilian/civil vs. military/militarized/militarists, understanding the role of elites and their leadership is a true barometer of the pulsating life of organisations[93].

The proceedings of elites and leadership has assumed a singularity in the history of peoples, which was no exception in the history of Portugal, often blending into the course of national institutions. How many historical testimonies give us an account of these legacies, fundamentally in key moments, where the affirmation, or not, of the elites and their respective options guided our common destiny. The same will happen with the elites and the civil police leadership among us, in parallel with the construction of an institutional culture, strongly imbedded of military history and culture[94], showing the interventions of numerous individuals in the events that marked this institutional (and civilisational) effort. Also, the need to update such historical studies today is evident, more than 150 years since the creation of the Public Security Police[95].

In Portugal, the police institution although markedly civil since its beginnings, followed the military organisational parameters and paths of its European counterparts throughout the 19th century and much of the 20th century[96], and its areas of expertise still remain very much a monopoly of military and police personnel.

According to the current state of affairs it is justified that military and police institutions are indispensable instruments at the service of the State in favour of internal cohesion and the external affirmation of Portugal. This was especially relevant during the Estado Novo and even after the Revolução dos Cravos[97]. Despite the profound political and social changes witnessed since 1974, the role of elites and leadership is felt as fundamental to reinforce an indoctrination of the national spirit, which is still imbedded in military and police values. On the contrary, the reinforcement of the Portuguese police image and identity gradually found its way through the efforts of the State apparatus itself, including the increasing performance of police forces in civil society even if they are not always subject to the proper scientific or historical historiography. Therefore, talking about the affinities and divergences between military and police institutions and elites will undoubtedly be an always incomplete endeavour, full of choices, trends, partialities, exaltations and omissions, but still essential for the understanding of the core and fundamental institutions at the base of the Rule of Law.

Based on a socio-historical approach, it was possible to understand the contribution of military leadership to the consolidation of police administrative elites, demarcating the current concept of “police leadership” and the characteristics of military inspiration in the Portuguese Police. Only by studying the past can we decode the present and project the future, an increasingly imperative challenge in the face of the emerging threats of the 21st century.

Almeida, F., 2013. As Elites de Portugal. Inadaptação, Crise e Desafios. Lisboa: Edições Vieira da Silva.

Almeida, P. T. and Marques, T. P., coord., 2006. Lei e Ordem. Justiça Penal, Criminalidade e Polícia (Séculos XIX-XX). Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

Alves, F. S. and Valente, A. M. C., 2006. Polícia de Segurança Pública: origem, evolução e atual missão. Politeia, III (1). Coimbra/Lisboa: Almedina/ICPOL-ISCPSI, 63–102.

Amaral, J. M. F., 1922. A mentira da Flandres… e o Mêdo! Lisboa: J. Rodrigues & Co.

Araújo, A., 2019. “Morte à PIDE!” A Queda da Polícia Política do Estado Novo. Lisboa: Tinta-da-China.

Araújo, E., 1898. Estudo historico sobre a Polícia da capital federal de 1808 a 1831. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional.

Bank, J., 1998. Qualidade Total – Manual de Gestão. Lisboa: Edições CETOP.

Bennis, W., 1998. Repensar a Liderança. In: R. Gibson, ed. Repensar o Futuro. Lisboa: Editorial Presença, 171–184.

Bertrand, Y. and Guillemet, P., 1988. Organizações: Uma Abordagem Sistémica. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 116–117.

Blin, J.-F., 1997. Les représentations professionnelles: un outil d’analyse du travail. Éducation Permanente. Revue internacionale de référence en formation des adultes, 132. Paris: EP, 159–170.

Borges, J. V., 2002. Liderança Militar. Lisboa: Edições Atena/Academia Militar.

Borges, J. V., 2011. A importância da formação em liderança nas Forças Armadas: subsídios para um modelo renovado, trabalho de investigação do Curso de Promoção a Oficial General. Lisboa: IESM.

Borges, J. V., dir., 2006. Contributos para o Pensamento Estratégico Português. Contributos (Sécs. XVI-XIX). Lisboa: Academia Militar/Editorial Prefácio.

Bru, M., 1992. Les variations didactiques dans l’organisation des conditions d’apprentissage. Toulouse: Éditions Universitaires du Sud.

Burns, J. M., 1978. Leadership. New York: Perenium.

Caetano, A. and Vala, J., dir., 2002. Gestão de Recursos Humanos: contextos, processos e técnicas. Lisboa: RH Editora.

Cardim, P., 1998. Cortes e cultura política no Portugal do Antigo Regime. Lisboa: Edições Cosmos.

Carrilho, L. M. R., 2005. Comandantes-Gerais e Diretores Nacionais da Polícia de Segurança Pública: 1935-2005. Politeia, II (1). Coimbra/Lisboa: Almedina/ICPOL-ISCPSI, 3159.

Cathrine Filstad & Tom Karp, 2020. Police leadership as a professional practice. Policing and Society. An International Journal of Research and Policy. London: Taylor & Francis.

Cosme, J., 2006. História da Polícia de Segurança Pública. Das origens à actualidade. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Crozier, M., 1994. A Empresa à Escuta. Lisboa: Intituto Piaget.

Cruz, M. A. and Guimarães, H., 2017. As Elites. História. Revista da FLUP, (IV), 7, 2. Porto: FLUP, 4–9.

Cruz, M. J. N., 2003. O sistema bipolar de segurança em Portugal: uma análise estratégica ao enquadramento dos corpos militares e civis de Polícia. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: Universidade Técnica.

Cunha, M. P. and Rodrigues, S. B., dir., 2002. Manual de Estudos Organizacionais. Temas de Psicologia, Psicolossociologia e Sociologia das Organizações. Lisboa: RH Editora.

Dias, H. V., 2012. Metamorfoses da Polícia: novos paradigmas de segurança e liberdade. Lisboa/Coimbra: ICPOL-ISCPSI/Almedina.

Dias, J. F. and Andrade, M. C., 1997. Criminologia: o Homem Delinquente e a Sociedade Criminógena. Coimbra: Coimbra Editora.

Dias, S., 2017. Um modo “português” de ser polícia. Cooperação policial e virtuosismo pós-colonial num mundo lusófono. Iberoamericana, XVII (64). Berlim: [s. n.].

Diridollou, B., 2002. Gerir a Sua Equipa Dia a Dia. Lisboa: Bertrand Editora.

Drucker, P. F., 1993. As Fronteiras da Gestão. Lisboa: Editorial Presença.

Duarte, V., 2005. Traços e perfis de cultura: estudo da cultura organizacional da Polícia de Segurança Pública de Braga. Master’s Thesis. Braga: ICS/Universidade do Minho.

Dubar, C., 2003. Formação, Trabalho e Identidades Profissionais. In: R. Canário, ed. Formação e Situações de Trabalho. Porto: Porto Editora, 43–52.

Duluc, A., 2000. Liderança e Confiança: desenvolver o capital humano para organizações competitivas. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget.

Durão, S., 2008. Patrulha e Proximidade. Uma Etnografia da Polícia em Lisboa. Lisboa/Coimbra: ICPOL-ISCPSI/Almedina.

Durão, S., 2016. Esquadra de Polícia. Lisboa: Fundação Manuel Francisco dos Santos.

Fachada, C. A., 2001. Liderança: percepção, formação e socialização no contexto do Ensino Superior Militar. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: ISCTE.

Farinha, L., coord., 2017. Morte à Morte! 150 anos de abolição da pena de morte em Portugal (1867-2017). Lisboa: Edições da Assembleia da República.

Faure G., 1991. Estrutura, Organização e Eficácia na Empresa. Mem-Martins: Edições CETOP.

Felgueiras, S. and Pais, L., 2017. Police commander’s education: a continuous process. European Police Science and Research Bulletin, 3. Luxembourg: CEPOL, Publications Office of the European Union, 179–185.

Ferreira, J. M. C., Neves, J. and Caetano, A., dir., 2001. Manual de Psicossociologia das Organizações. Lisboa: McGraw-Hill.

Fonseca, L. A., 2005. D. João II. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores.

Fouquet, C. L., 1869. Instruction du Maréchal de Belle-Isle sur les Devoirs du Chef Militaire. Paris: Libraire Militaire de J. Dumaine.

Freire, J., 2002. Sociologia do Trabalho. Uma Introdução. Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

Freitas, J. P., 2007. O Combatente durante a Guerra da Restauração. Vivência e comportamentos dos militares ao serviço da Coroa portuguesa (1640-1668). Lisboa: Prefácio.

Giddens, A., 2009. Sociologia. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Goleman, D., 2010. Inteligência Emocional. Lisboa: Temas & Debates/Círculo de Leitores.

Gomes, A., and Castanheira, J. P., 2006. Os dias loucos do PREC: do 11 de Março ao 25 de Novembro de 1975. Lisboa: Público/Expresso.

Gonçalves, G. R. and Durão, S., orgs., 2017. Polícia e Polícias em Portugal. Perspetivas Históricas. Lisboa: Editora Mundos Sociais.

Guerra, I., 2002. Fundamentos e Processos de uma Sociologia de Acção. O Planeamento em Ciências Sociais. Cascais: Principia.

Handy, C., 1996. A Era da Incerteza. Uma reflexão sobre as transformações em curso na sociedade moderna. Mem-Martins: Edições CETOP.

Harig, C., 2019. Soldiers in police roles. Policing and Society. An International Journal of Research and Policy. London: Taylor & Francis.

Higley, J., 2010. Elites e Democracia. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

Homem, A. L. C., 1990. Portugal nos finais da Idade Média: Estado, Instituições, Sociedade Política.

Hossain, N. and Moore, M., 2002. Arguing for the poor: elites and poverty in developing countries. IDS Working Paper, 148. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies.

Justino, D., 2016. Fontismo: Liberalismo numa Sociedade Iliberal. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote.

L’Heuillet, H., 2004. Alta Polícia, Baixa Política. Uma visão sobre a Polícia e a relação com Poder. Lisboa: Notícias Editorial.

Landier, H., 1994. Para uma empresa inteligente. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget.

Leal, M., 2017. Visconde de Seabra. Autor do primeiro Código Civil Português. Lisboa: Alêtheia Editores.

Leitão, D. V. and Rosinha, A., 2007. Manual de Ética e Liderança: uma visão militar e académica. Lisboa: Academia Militar.

Lourenço, E., 1996. Cultura e Política na época marcelista. Lisboa: Cosmos.

Luís, A. M., 2007. Comando e Chefia-Liderança: o Líder Impuro. Proelium, (VI), 6. Lisboa: Academia Militar, 47–78.

Magalhães, D. S., 2006. A liderança em contexto de mudança organizacional na Polícia de Segurança Pública (PSP) do Porto: representação dos deveres-valores no exercício das funções de supervisor operacional. Master’s Thesis. Porto: Escola de Criminologia da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade do Porto.

Marques, A. H. O., coord., 1991. A Revolução de 31 de Janeiro de 1891. Lisboa: Biblioteca Nacional.

Marques, C. A. and Cunha, M. P., coord., 2000. Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão de Empresas. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote.

Maxwell, J. C., 2010. O Líder 360º. Desenvolvendo a sua influência a partir de qualquer ponto da organização. Lisboa: SmartBook.

Mendonça, M., 2009. D. João II, o Príncipe Perfeito. Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa da História.

Michel, S., 1993. Gestão das Motivações. Porto: Rés Editora.

Michels, R., 1914. Les Partis Politiques. Essai sur les tendances oligarchiques des démocraties. Paris: Flammarion.

Mills, C. W., 1956. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Mills, C. W., 1981. A Elite do Poder. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar Editores.

Mineiro, S. P. N., 2013. Motivação, Comunicação e Liderança: o caso da Polícia de Segurança Pública. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: ISCAL-IPL.

Mintzberg, H., 1999. Estrutura e Dinâmica das Organizações. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote.

Monteiro, N. F., 2003. Elites e Poder entre o Antigo Regime e o Liberalismo. Lisboa: Instituto de Ciências Sociais.

Mosca, G., 1953. Elementi di Scienza Politica. Bari: Editori Laterza.

Moura, R. C. and Ramalho, N. C., 2017. Adressing emotions in police selection and initial training: a european study. European Police Science and Research Bulletin, 16. Luxembourg: CEPOL, Publications Office of the European Union, 119–141.

Muirequetule, V., 2017. Ensino Superior Militar e desenvolvimento de competências de comando e liderança. Thesis (PhD). Lisboa: Universidade Católica Portuguesa.

Neves, A. L., 2002. Motivação para o Trabalho. Lisboa: RH Editora.

Neves, J. G., 2000. Clima Organizacional, Cultura Organizacional e Gestão de Recursos Humanos. Lisboa: RH Editora.

Nunes, M. R. A., 2012. Os Diretores-Gerais: o recrutamento das elites administrativas no Portugal democrático. Thesis (PhD). Lisboa: ICS-UL.

Oliveira, J. et al., N., 2010. Estudo sobre a Polícia de Segurança Pública: uma linha estratégica de mudança dirigida à missão, ao enriquecimento do tecido social da organização, à melhoria da burocracia e ao aproveitamento dos recursos. Lisboa: DNPSP.

Pais, S., 1943. A PSP: Fôrça ao Serviço da Ordem. Polícia Portuguesa, 35. Lisboa: Comando Geral da PSP.

Pareto, V., 1968. Traité de Sociologie Générale. In: G. Busino, ed. Œuvres Complètes, XII. Genève: Droz.

Passos, M. L. F., 2014. Lisboa. A Cidade de Fernão Lopes. Lisboa: Edições Colibri.

Paymal, F., 2008. La Construction identitaire de l’élève à l’Instituto Superior de Ciências Policiais e Segurança Interna (ISCPSI)/École Supérieure de Police Portugaise. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa.

Penteado, J. R. W., 1993. Relações Públicas nas Empresas Modernas. São Paulo: Editora Pioneira.

Peters, T. and Waterman, B., 1995. Na Senda da Excelência: o exemplo das empresas norte-americanas mais bem geridas. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote.

Poiares, N., 2005a, A profissão polícia: um constructo contínuo da representação social. In: F. M. Ramos and C. A. Silva, orgs., Sociologia em Diálogo II. Évora: CISA-AS/Universidade de Évora, 73–96.

Poiares, N., 2005b. Na encruzilhada das competências: autoridade e ordem ou serviço social? Um estudo de caso no Alentejo. Politeia. Lisboa/Coimbra: ICPOL-ISCPSI/Almedina, 62–79.

Poiares, N., 2013. Mudar a Polícia ou mudar os polícias? O papel da PSP na sociedade portuguesa. Lisboa: Bnomics.

Poiares, N., 2018. As profissões (para)jurídicas em Portugal: requisitos, mandatos e convergências. Porto: Fronteira do Caos Editores.

Polícia Portuguesa (1971), 207. Lisboa: Comando Geral da PSP.

Programa do Movimento das Forças Armadas Portuguesas (1975). Lisboa: Junta de Salvação Nacional.

Queffelec, C., 2018. O papel das Forças Armadas Francesas sobre o território nacional no âmbito do terrorismo. In: N. Poiares and R. Marta, coord., Segurança Interna: desafios na sociedade de risco mundial. Lisboa: ISCPSI, 67–75.

Ribeiro, M. C., 2000. A Polícia Política no Estado Novo (1926-1945). Lisboa: Editorial Estampa.

Rosa, L., 1994. Cultura Empresarial. Motivação e Liderança – Psicologia das Organizações. Lisboa: Editorial Presença.

Rosinha, A. P. and Matias, L. S., coord., 2015. Casos de Liderança em contexto militar: a prática à luz da teoria. Lisboa: Instituto de Estudos Superiores Militares.

Sainsaulieu, R., 1997. Sociologia da Empresa. Organização, Cultura e Desenvolvimento. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget.

Santos, A. P. R., 1999. O Estado e a Ordem Pública. As Instituições Militares Portuguesas. Lisboa: ISCSP.

Santos, L. B., 2014. Subsídio para um referencial de competências destinado ao exercício de liderança no contexto das Forças Armadas portuguesas. Lisboa: Instituto de Estudos Superiores Militares.

Serrão, J., 1990. Da Regeneração à República. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

Silva, A. M. C., 2003. Formação, Percursos e Identidades. Coimbra: Quarteto.

Silva, N. M. P., 2017. Between the Military and the Police: Public Security Police and National Republican Guard Officer’s attitudes to Public Administration Policies. European Police Science and Research Bulletin, 16. Luxembourg: CEPOL, Publications Office of the European Union, 169–186.

Teixeira, N. S., 1990. O Ultimatum Inglês. Política externa e política interna no Portugal de 1890. Lisboa: Publicações Alfa.

Teixeira, S., 1998. Gestão das Organizações. Amadora: McGraw-Hill.

Thévenet, M., 1997. Cultura da Empresa. Auditoria e Mudança. Lisboa: Monitor.

Treviño, J. G. G., 2001. Administración Contemporánea. Ciudad de Mexico: McGraw-Hill.

Ventura, A. 2006. Campanhas Coloniais. Angola, Moçambique, Guiné e Timor (1850-1925). Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa de História.

Ventura, A., 2010. D. Luís, o Popular. Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa da História.

Vieira, B., 2002. Manual de Liderança Militar. Lisboa: Academia Militar.

Legislation

Lei n.º 5/99, de 27 de janeiro.

Decreto-Lei n.º 423/82, de 15 de outubro.

Decreto-Lei n.º 151/85, de 9 de maio.

Decreto-Lei n.º 321/94, de 29 de dezembro.

Decreto-Lei n.º 2-A/96, de 13 de janeiro.

Decreto-Lei n.º 137/2019, de 13 de setembro.

Portaria n.º 123/2011, de 30 de março.

Despacho n.º 08/GDN/2009, de 28 de abril de 2009.

Links

https://rr.sapo.pt/2020/04/23/pais/ligou-me-a-pedir-desculpa-afinal-o-que-se-passa-entre-o-exercito-e-a-psp/noticia/190330/ [acessed 29 June 2020].

https://www.jn.pt/justica/diretor-nacional-da-psp-desmente-chefe-das-forcas-armadas-12108087.html [acessed 29 June 2020].

[1] *Agregado e Doutor em História. Professor Auxiliar com Agregação do ISCPSI e Investigador Integrado do ICPOL-ISCPSI.

** Doutor em Sociologia e Especialista em Direito Penal. Intendente da PSP, Professor do ISCPSI e Investigador Integrado do ICPOL-ISCPSI.

This crisis culminated in Dispatch no. 08/GDN/2009, of April 28, 2009, by the National Director of PSP, Chief Superintendent Francisco Oliveira Pereira, who created the “SWOT” working group, a tool for the analysis scenarios and environments. Its aim was to understand the view of the internal public regarding the future of the PSP. For a deeper understanding of the SWOT concept, vide Guerra, I., 2002. Fundamentos e Processos de uma Sociologia de Acção. O Planeamento em Ciências Sociais. Cascais: Principia.

[2] Judge Mário Belo Morgado took office as National Director on August 5, 2002, followed by Judge José Branquinho Lobo and State Attorney Orlando Soares Romano.

[3] Chief Superintendents Francisco Oliveira Pereira (2008-2011) and Guilherme Guedes da Silva (2011-2012).

[4] Chief Superintendents Paulo Jorge Valente Gomes (2012-2013), Luís Manuel Peça Farinha (2013-2020) and Manuel Augusto Magina da Silva (since 2020).

[5] Fachada, C. A., 2001. Liderança: percepção, formação e socialização no contexto do Ensino Superior Militar. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: ISCTE; Vieira, B., 2002. Manual de Liderança Militar. Lisboa: Academia Militar; Santos, L. B., 2014. Subsídio para um referencial de competências destinado ao exercício de liderança no contexto das Forças Armadas portuguesas. Lisboa: Instituto de Estudos Superiores Militares; Muirequetule, V., 2017. Ensino Superior Militar e desenvolvimento de competências de comando e liderança. Thesis (PhD). Lisboa: Universidade Católica Portuguesa.

[6] The Escola Superior de Polícia was created by Decree-Law no. 423/82, of October 15, and started its activities in the academic year 1984-1985.

[7] The five-year academic course, with a strong legal component, began with the designation of Police Science and students were treated as cadets, similar to the Military Science course taught at the Military Academy. With the Bologna reform, the course started in 2009, to be called integrated masters in Police Sciences. However, from 2021 the course will be divided into two cycles: a degree in Police Science (3 years) and a Masters in Public Security (2 years).

[8] The General Command changed its name to National Directorate, just as the Higher Police School became the Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, and the hierarchical pyramid would suffer a flattening in the face of the extinction of several categories, stipulated by Law no. 5/99, of 27 January.

[9] Cruz, M. A. and Guimarães, H., 2017. As Elites. História. Revista da FLUP, (IV), 7, 2. Porto: FLUP, 4-9.

[10] Hossain, N. and Moore, M., 2002. Arguing for the poor: elites and poverty in developing countries. IDS Working Paper, 148. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies.

[11] Almeida, F., 2013. As Elites de Portugal. Inadaptação, Crise e Desafios. Lisboa: Edições Vieira da Silva.

[12] Mills, C. W., 1956. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.; Mills, C. W., 1981. A Elite do Poder. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar Editores.

[13] Almeida, F., 2013. As Elites de Portugal. Inadaptação, Crise e Desafios.

[14] Nunes, M. R. A., 2012. Os Diretores-Gerais: o recrutamento das elites administrativas no Portugal democrático. Thesis (PhD). Lisboa: ICS-UL.

[15] Exception made, e.g., to Carrilho, L. M. R., 2005. Comandantes-Gerais e Diretores Nacionais da Polícia de Segurança Pública: 1935-2005. Politeia, II (1). Coimbra/Lisboa: Almedina/ICPOL-ISCPSI, 31–59; Poiares, N., 2013. Mudar a Polícia ou mudar os polícias? O papel da PSP na sociedade portuguesa. Lisboa: Bnomics.

[16] Mintzberg, H., 1999. Estrutura e Dinâmica das Organizações. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote.

[17] Ferreira, J. M. C., Neves, J. and Caetano, A., dir., 2001. Manual de Psicossociologia das Organizações. Lisboa: McGraw-Hill.

[18] Landier, H., 1994. Para uma empresa inteligente. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 95-107; Handy, C., 1996. A Era da Incerteza. Uma reflexão sobre as transformações em curso na sociedade moderna. Mem-Martins: Edições CETOP, 113-115.

[19] Goleman, D., 2010. Inteligência Emocional. Lisboa: Temas & Debates/Círculo de Leitores.

[20] Bank, J., 1998. Qualidade Total – Manual de Gestão. Lisboa: Edições CETOP.

[21] Landier, H., 1994. Para uma empresa inteligente; Diridollou, B., 2002. Gerir a Sua Equipa Dia a Dia. Lisboa: Bertrand Editora, 123–125; Treviño, J. G. G., 2001. Administración Contemporánea. Ciudad de Mexico: McGraw-Hill, 362–384; Cunha, M. P. and Rodrigues, S. B., dir., 2002. Manual de Estudos Organizacionais. Temas de Psicologia, Psicolossociologia e Sociologia das Organizações. Lisboa: RH Editora.

[22] Duluc, A., 2000. Liderança e Confiança: desenvolver o capital humano para organizações competitivas. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 82–83.

[23] Crozier, M., 1994. A Empresa à Escuta. Lisboa: Intituto Piaget.

[24] Michel, S., 1993. Gestão das Motivações. Porto: Rés Editora.

[25] Peters, T. and Waterman, B., 1995. Na Senda da Excelência: o exemplo das empresas norte-americanas mais bem geridas. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote, 251.

[26] Maxwell, J. C., 2010. O Líder 360º. Desenvolvendo a sua influência a partir de qualquer ponto da organização. Lisboa: SmartBook.

[27] Mineiro, S. P. N., 2013. Motivação, Comunicação e Liderança: o caso da Polícia de Segurança Pública. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: ISCAL-IPL, 49.

[28] Luís, A. M., 2007. Comando e Chefia-Liderança: o Líder Impuro. Proelium, (VI), 6. Lisboa: Academia Militar, 75.

[29] Burns, J. M., 1978. Leadership. New York: Perenium.

[30] Bennis, W., 1998. Repensar a Liderança. In: R. Gibson, ed. Repensar o Futuro. Lisboa: Editorial Presença, 171–184.

[31] Rosa, L., 1994. Cultura Empresarial. Motivação e Liderança – Psicologia das Organizações. Lisboa: Editorial Presença, 122.

[32] Locke, E. A., Motowidlo, S. J. and Bobko, P., 1986, apud Neves, A. L., 2002. Motivação para o Trabalho. Lisboa: RH Editora, 77.

[33] Drucker, P. F., 1993. As Fronteiras da Gestão. Lisboa: Editorial Presença, 148.

[34] Fouquet, C. L., 1869. Instruction du Maréchal de Belle-Isle sur les Devoirs du Chef Militaire. Paris: Libraire Militaire de J. Dumaine.

[35] Borges, J. V., 2002. Liderança Militar. Lisboa: Edições Atena/Academia Militar, 11.

[36] Idem, ibidem.

[37] Borges, J. V., 2011. A importância da formação em liderança nas Forças Armadas: subsídios para um modelo renovado, trabalho de investigação do Curso de Promoção a Oficial General. Lisboa: IESM, 9.

[38] Luís, A. M., 2007. Comando e Chefia-Liderança: o Líder Impuro. Proelium, (VI), 6, 73.

[39] Idem, 6, 69.

[40] Dias, J. F. and Andrade, M. C., 1997. Criminologia: o Homem Delinquente e a Sociedade Criminógena. Coimbra: Coimbra Editora, 443.

[41] Giddens, A., 2009. Sociologia. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 224-225.

[42] Moura, R. C. and Ramalho, N. C., 2017. Adressing emotions in police selection and initial training: a european study. European Police Science and Research Bulletin, 16. Luxembourg: CEPOL, Publications Office of the European Union, 119-141; Felgueiras, S. and Pais, L., 2017. Police commander’s education: a continuous process. European Police Science and Research Bulletin, 3. Luxembourg: CEPOL, Publications Office of the European Union, 179-185.

[43] Cathrine Filstad & Tom Karp, 2020. Police leadership as a professional practice. Policing and Society. An International Journal of Research and Policy. London: Taylor & Francis.

[44] L’Heuillet, H., 2004. Alta Polícia, Baixa Política. Uma visão sobre a Polícia e a relação com Poder. Lisboa: Notícias Editorial, 216.

[45] Penteado, J. R. W., 1993. Relações Públicas nas Empresas Modernas. São Paulo: Editora Pioneira, 24-33.

[46] Sainsaulieu, R., 1997. Sociologia da Empresa. Organização, Cultura e Desenvolvimento. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 135.

[47] Bertrand, Y. and Guillemet, P., 1988. Organizações: Uma Abordagem Sistémica. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 116-117; Faure G., 1991. Estrutura, Organização e Eficácia na Empresa. Mem-Martins: Edições CETOP, 103-122; Sainsaulieu, R., 1997. Sociologia da Empresa. Organização, Cultura e Desenvolvimento; Thévenet, M., 1997. Cultura da Empresa. Auditoria e Mudança. Lisboa: Monitor; Teixeira, S., 1998. Gestão das Organizações. Amadora: McGraw-Hill; Neves, J. G., 2000. Clima Organizacional, Cultura Organizacional e Gestão de Recursos Humanos. Lisboa: RH Editora; Marques, C. A. and Cunha, M. P., coord., 2000. Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão de Empresas. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote; Caetano, A. and Vala, J., dir., 2002. Gestão de Recursos Humanos: contextos, processos e técnicas. Lisboa: RH Editora.

[48] The History of PJ, the Portuguese security service with competence in the area of criminal investigation, is associated with the judiciary, while the PSP is linked to the military elites. The organizational structure of the PJ was approved by Decree-Law no. 137/2019, of 13 September, which states, in its preamble, that the headquarters of the PJ is based on its primary mission in assisting the judiciary, especially the Ministry Public.

[49] Oliveira, J. et al., 2010. Estudo sobre a Polícia de Segurança Pública: uma linha estratégica de mudança dirigida à missão, ao enriquecimento do tecido social da organização, à melhoria da burocracia e ao aproveitamento dos recursos. Lisboa: DNPSP.

[50] Dias, H. V., 2012. Metamorfoses da Polícia: novos paradigmas de segurança e liberdade. Lisboa/Coimbra: ICPOL-ISCPSI/Almedina, 124.

[51] Poiares, N., 2005b. Na encruzilhada das competências: autoridade e ordem ou serviço social? Um estudo de caso no Alentejo. Politeia. Lisboa/Coimbra: ICPOL-ISCPSI/Almedina, 62-79.

[52] Dias, H. V., 2012. Metamorfoses da Polícia: novos paradigmas de segurança e liberdade, 162.

[53] The first two women to reach the category of superintendent (colonel) were Madalena de Almeida Amaral and Paula Cristina Peneda, both from the 2nd Police Officer Training Course. However, there is still a challenge to be met: a woman in the category of chief superintendent (general) and, by this means, to be appointed the first National Director.

[54] Alves, F. S. and Valente, A. M. C. 2006. Polícia de Segurança Pública: origem, evolução e atual missão. Politeia, III (1). Coimbra/Lisboa: Almedina/ICPOL-ISCPSI, 63–102.

[55] Durão, S., 2016. Esquadra de Polícia. Lisboa: Fundação Manuel Francisco dos Santos, 103.

[56] Leitão, D. V. and Rosinha, A., 2007. Manual de Ética e Liderança: uma visão militar e académica. Lisboa: Academia Militar.

[57] Poiares, N., 2005a, A profissão polícia: um constructo contínuo da representação social. In: F. M. Ramos and C. A. Silva, orgs., Sociologia em Diálogo II. Évora: CISA-AS/Universidade de Évora, 73–96; Poiares, N., 2005b. Na encruzilhada das competências: autoridade e ordem ou serviço social? Um estudo de caso no Alentejo. Politeia, 62-79; Durão, S., 2008. Patrulha e Proximidade. Uma Etnografia da Polícia em Lisboa. Lisboa/Coimbra: ICPOL-ISCPSI/Almedina; Poiares, N., 2013. Mudar a Polícia ou mudar os polícias? O papel da PSP na sociedade portuguesa; Gonçalves, G. R. and Durão, S., 2017, orgs., Polícia e Polícias em Portugal. Perspetivas Históricas. Lisboa: Editora Mundos Sociais; Poiares, N., 2018. As profissões (para)jurídicas em Portugal: requisitos, mandatos e convergências. Porto: Fronteira do Caos Editores.

[58] Freire, J., 2002. Sociologia do Trabalho. Uma Introdução. Porto: Edições Afrontamento, 329.

[59] Bru, M., 1992. Les variations didactiques dans l’organisation des conditions d’apprentissage. Toulouse: Éditions Universitaires du Sud.

[60] Blin, J.-F., 1997. Les représentations professionnelles: un outil d’analyse du travail. Éducation Permanente. Revue internacionale de référence en formation des adultes, 132. Paris: EP, 159-170; Silva, A. M. C., 2003. Formação, Percursos e Identidades. Coimbra: Quarteto, 87.

[61] Dubar, C., 2003. Formação, Trabalho e Identidades Profissionais. In: R. Canário, ed. Formação e Situações de Trabalho. Porto: Porto Editora, 43–52.

[62] Justino, D., 2016. Fontismo: Liberalismo numa Sociedade Iliberal. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote.

[63] Serrão, J., 1990. Da Regeneração à República. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

[64] Teixeira, N. S., 1990. O Ultimatum Inglês. Política externa e política interna no Portugal de 1890. Lisboa: Publicações Alfa.

[65] Marques, A. H. O., coord., 1991. A Revolução de 31 de Janeiro de 1891. Lisboa: Biblioteca Nacional.

[66] Ventura, A., 2010. D. Luís, o Popular. Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa da História.

[67] Almeida, P. T. and Marques, T. P., coord., 2006. Lei e Ordem. Justiça Penal, Criminalidade e Polícia (Séculos XIX-XX). Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

[68] Ventura, A. 2006. Campanhas Coloniais. Angola, Moçambique, Guiné e Timor (1850-1925). Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa de História.

[69] Farinha, L., coord., 2017. Morte à Morte! 150 anos de abolição da pena de morte em Portugal (1867-2017). Lisboa: Edições da Assembleia da República.

[70] Leal, M., 2017. Visconde de Seabra. Autor do primeiro Código Civil Português. Lisboa: Alêtheia Editores.

[71] Alves, F. S. and Valente, A. M. C. 2006. Polícia de Segurança Pública: origem, evolução e atual missão. Politeia, III (1), 63–102.

[72] Idem.

[73] Polícia Portuguesa (1971), 207. Lisboa: Comando Geral da PSP, 8.

[74] Amaral, J. M. F., 1922. A mentira da Flandres… e o Mêdo! Lisboa: J. Rodrigues & Co.

[75] Pais, S., 1943. A PSP: Fôrça ao Serviço da Ordem. Polícia Portuguesa, 35. Lisboa: Comando Geral da PSP, 13; Carrilho, L. M. R., 2005. Comandantes-Gerais e Diretores Nacionais da Polícia de Segurança Pública: 1935-2005. Politeia, II (1), 31-59.

[76] Ribeiro, M. C., 2000. A Polícia Política no Estado Novo (1926-1945). Lisboa: Editorial Estampa.

[77] Araújo, A., 2019. “Morte à PIDE!” A Queda da Polícia Política do Estado Novo. Lisboa: Tinta-da-China.

[78] Lourenço, E., 1996. Cultura e Política na época marcelista. Lisboa: Cosmos.

[79] Cruz, M. J. N., 2003. O sistema bipolar de segurança em Portugal: uma análise estratégica ao enquadramento dos corpos militares e civis de Polícia. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: Universidade Técnica.

[80] Gomes, A., and Castanheira, J. P., 2006. Os dias loucos do PREC: do 11 de Março ao 25 de Novembro de 1975. Lisboa: Público/Expresso.

[81] Decreto-Lei n.º 423/82, de 15 de outubro.

[82] Decreto-Lei n.º 151/85, de 9 de maio.

[83] Decreto-Lei n.º 321/94, de 29 de dezembro.

[84] Decreto-Lei n.º 2-A/96, de 13 de janeiro.

[85] Carrilho, L. M. R., 2005. Comandantes-Gerais e Diretores Nacionais da Polícia de Segurança Pública: 1935-2005. Politeia, II (1), 31–59.

[86] Paymal, F., 2008. La Construction identitaire de l’élève à l’Instituto Superior de Ciências Policiais e Segurança Interna (ISCPSI)/École Supérieure de Police Portugaise. Master’s Thesis. Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa.

[87] Silva, N. M. P., 2017. Between the Military and the Police: Public Security Police and National Republican Guard Officer’s attitudes to Public Administration Policies. European Police Science and Research Bulletin, 16. Luxembourg: CEPOL, Publications Office of the European Union, 184.

[88] Aprovado pela Portaria n.º 123/2011, de 30 de março. Diário da República, 1.ª série, n.º 63.

[89] Harig, C., 2019. Soldiers in police roles. Policing and Society. An International Journal of Research and Policy. London: Taylor & Francis.

[90] Queffelec, C., 2018. O papel das Forças Armadas Francesas sobre o território nacional no âmbito do terrorismo. In: N. Poiares and R. Marta, coord., Segurança Interna: desafios na sociedade de risco mundial. Lisboa: ISCPSI, 67–75.

[91] Vide https://rr.sapo.pt/2020/04/23/pais/ligou-me-a-pedir-desculpa-afinal-o-que-se-passa-entre-o-exercito-e-a-psp/noticia/190330/ e https://www.jn.pt/justica/diretor-nacional-da-psp-desmente-chefe-das-forcas-armadas-12108087.html [acessed 29 June 2020].

[92] Rosinha, A. P. and Matias, L. S., coord., 2015. Casos de Liderança em contexto militar: a prática à luz da teoria. Lisboa: Instituto de Estudos Superiores Militares.

[93] Magalhães, D. S., 2006. A liderança em contexto de mudança organizacional na Polícia de Segurança Pública (PSP) do Porto: representação dos deveres-valores no exercício das funções de supervisor operacional. Master’s Thesis. Porto: Escola de Criminologia da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade do Porto.

[94] Borges, J. V., dir., 2006. Contributos para o Pensamento Estratégico Português. Contributos (Sécs. XVI-XIX). Lisboa: Academia Militar/Editorial Prefácio.

[95] Duarte, V., 2005. Traços e perfis de cultura: estudo da cultura organizacional da Polícia de Segurança Pública de Braga. Master’s Thesis. Braga: ICS/Universidade do Minho.

[96] Santos, A. P. R., 1999. O Estado e a Ordem Pública. As Instituições Militares Portuguesas. Lisboa: ISCSP.

[97] Durão, S., 2017. Um modo “português” de ser polícia. Cooperação policial e virtuosismo pós-colonial num mundo lusófono. Iberoamericana, XVII (64). Berlim: [s. n.].

Agregado e Doutor em História. Professor Auxiliar com Agregação do ISCPSI e Investigador Integrado do ICPOL-ISCPSI.

Doutor em Sociologia e Especialista em Direito Penal. Intendente da PSP, Professor do ISCPSI e Investigador Integrado do ICPOL-ISCPSI.