Nº 2535 - Abril de 2013

Pessoa coletiva com estatuto de utilidade pública

Introduction

This article analyzes the various aspects of Chinese maritime strategy. Why this subject? It should be noted that considerable attention has been bestowed – by the media, but also by the commentators of modern geopolitics – upon China’s economic emergence. Indeed, the economy has been growing at a remarkable pace over the past few years. On the other hand, it is relatively consensual that the Middle Kingdom vehemently seeks to diversify its energy sources.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that there are other aspects in the context of the emergence of the Chinese giant, which cannot be sidelined, as they, directly or indirectly, also enhance/contribute to the rise of China in the complex chessboard of world powers, and more specifically, to the judgment and perception that the international community produces about that same emergence. That said, this article focuses on giving greater visibility to an issue sometimes overlooked by commentators on international relations, which is precisely the potential and the maritime strategy of a rising power, in this case, China. Earth, Air and Sea, there are three spheres of action that a demographic and economic power like China cannot neglect if it intends to enjoy an even more prominent role in major decisions affecting the fate of the new century, as well as the structure of the International System, unstable and evolving over the last years. If, on the one hand, as stated by Zhao Huasheng (2009: 475), “geopolitics is largely determined by the dimensions of a region”, considering that, in practice, “the major powers need to acquire a large land mass to exert influence on the international chessboard”, one should also not deviate attention from what is happening in the seas. In this regard, Alfred Mahan (to whom we will refer to later), emphasizes the importance of waterways in what regards the protection of world trade. However, China seems to realize (as we shall see) how important it is to have a navy capable of protecting its merchant navy. However, the Chinese are also aware of the importance of mitigating the “geopolitical vulnerabilities” of a trade based on energy imports, which depends on shipping lines, and may, for that very reason, prove to be unsafe in the event of a maritime blockade” (Kenny, 2004: 42). As Kenny (2004: 43) explains, “since more than three quarters of China’s oil imports will pass through the Strait of Malacca by the year 2025, China has sought alternatives”. Although resorting to energy imports from Central Asia through pipelines proves that Beijing has paid attention to the issue of energy security, by land is, by itself, clearly insufficient to ensure the energy (but not only energy) supply of China. Hence, the importance of the sea and therefore, of a comprehensive sea strategy, which this reflection seeks to emphasize.

That said, we will structure this article around some issues that seem very relevant with regard to the Chinese stance towards the sea. We will seek to address the key features of the new naval diplomacy of the Middle Kingdom. In this sense, we will highlight the importance of a set of islands, archipelagos and sea passages within the Chinese maritime strategy, referring, on the other hand, to the well-known ‘String of Pearls’ project. We will seek to highlight the main objectives for China of what we call a ‘new Chinese naval doctrine’. What aspects does it encompass in practice? What implications and changes does it entail? Does it, indeed, refer to an evolution of Chinese maritime thinking? Is Chinese naval behaviour more pragmatic and assertive today than in the past? How do the assumptions of Alfred Mahan reflect themselves in China’s view of the sea? Do the trends of the Chinese Navy reveal a growing attempt to modernize? We will try to answer these questions as we proceed in our reasoning. Moreover, since the sea is also a good indicator of the relationships between the various players, this paper seeks to highlight the case of Taiwan and India in particular. Why is Taiwan strategically (at least from a sea viewpoint) so important to Beijing? And, on the other hand, how do the Sino-Indian power strategies manifest themselves in the Indian Ocean? These are some of the other issues that we intend to discuss.

By addressing the several topics aforementioned, which are, nevertheless, closely related to what China expects from the sea, this article will try to demonstrate that Chinese leaders seem to be aware that a power that does not understand the importance of oceans is a power without future.

Chinese maritime strategy

The Chinese official discourse, extroverted, pragmatic, of a power that is developing in a ‘peaceful’ and ‘harmonious’ way, aims to “open China to the world and, in particular, the world to China” (Zajec, 2008: 2). It is therefore not surprising that Chinese soft power also follows the path of the sea. It is in this context that 2007 witnessed a new ‘naval diplomacy’. Indeed, Chinese ships have made official visits to Singaporean, Australian, Japanese, Russian, North American, French and Spanish ports, and have also participated in international manoeuvres in the struggle against maritime piracy (Medeiros, 2007). The question that such an unprecedented initiative raises, at a first glance, is: What does China expect from the sea?

Certainly, the South China Sea is rich in hydrocarbons and varieties of fish, but it is not only such resources that Beijing looks for. Indeed, China seems to be equally concerned with (re)defining the scope of its Exclusive Economic Zone and with its claims over Taiwan. In addition, the Middle Kingdom also seeks to ensure the access of its fleet to the open seas, including the maritime corridors of South East Asia, beyond the Indochinese peninsula (Buszynski, 2012). Obviously, one must not forget the need to protect the sea lines of energy supply which are absolutely vital for a China that is currently the second largest oil importing country in the world (Zajec, 2008). If this worries some countries in the regional and global sphere, some authors such as Rizzi (2009: 17), however, do not see in this anything unusual, especially since «what the Chinese are doing has already been done by the United States from 1946».

Archipelagos and crucial passages

In addition to the claims over Taiwan, Beijing’s ambitions aim to control a series of islands and islets, fundamental pieces in the chessboard of its maritime strategy. The case of Taiwan, as we shall see later, is unquestionable, as Beijing is determined to recover its sovereignty over the territory, even if it means using its military power. Certainly, China endeavours to increasingly modernize its navy, by reducing the technology gap between it and the most developed fleets. Nevertheless, on the other hand, as Olivier Zajec (2008: 10) stresses, “the U.S. Navy is concerned with the psychological monitoring of the inevitable evolution that should lead to the peaceful return of Taiwan to the motherland”.

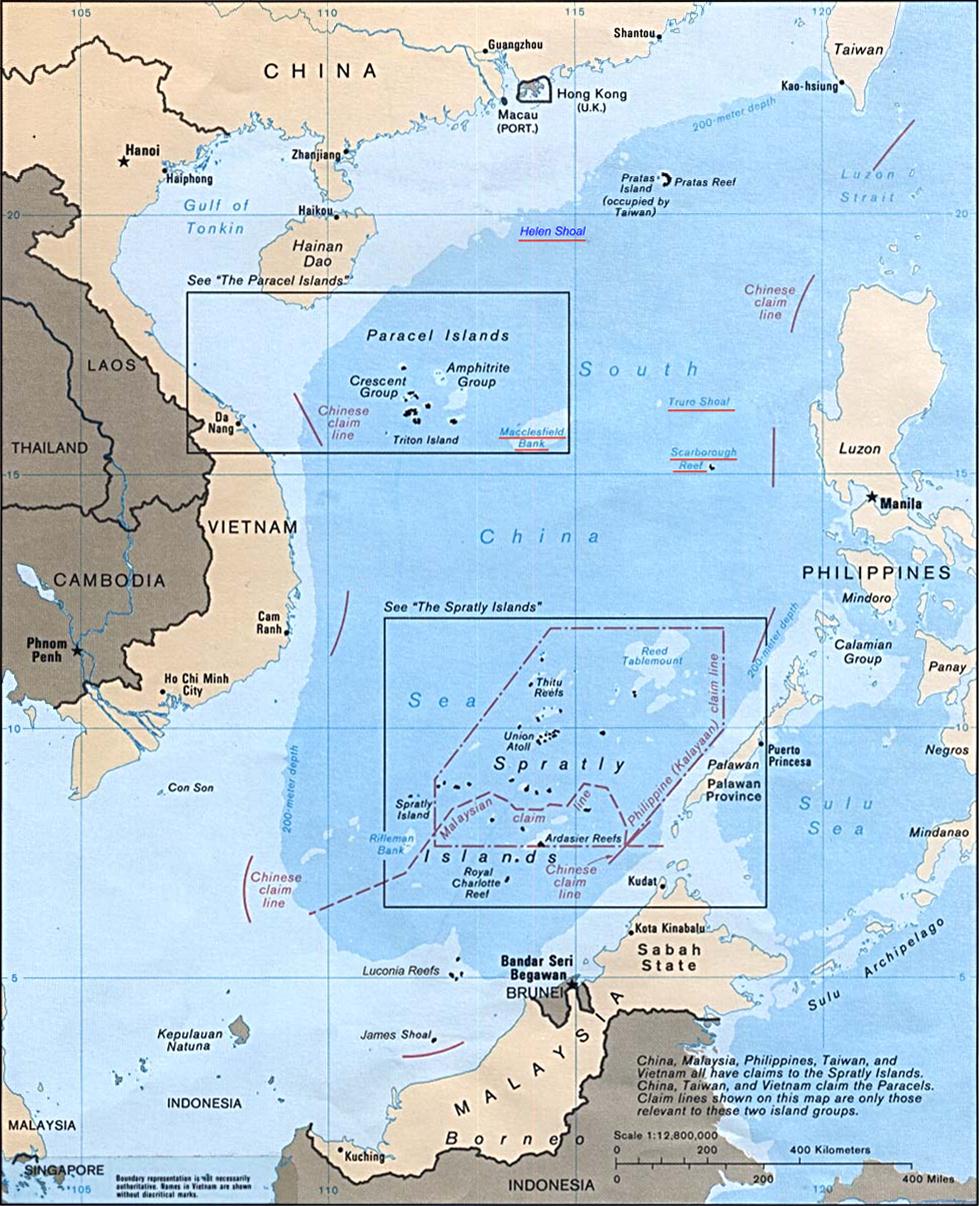

However, it is not only Taiwan. With Japan, for example, China has disputes regarding the Diaoyutai Islands, which also serve as shelter to a U.S. military base (Franco, 2007). With Vietnam, Taiwan, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia, disputes exist over the Pratas (Dongsha), Paracel (Xisha) and Spratly (Nansha) archipelagos (Wood, 2012). These are extremely important for China, not only because of the existence of gas, oil and fishery resources (which is often Beijing’s official justification for the Chinese navy to cross these regions), but also due to their strategic location. In addition to controlling the sea lines linking the Far East to other places on the planet, these territories are also «a good location to house technical guidance radar and to monitor ships that cross the China Sea» (Franco, 2007: 12).

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org

However, the Chinese maritime strategy is not limited to the Pacific Ocean. Since China fears “a U.S. oil embargo in the event of conflict over the return of Taiwan to the motherland”, it has turned to “the formation of ground support points responsible for protecting its supply routes” (Ranade, 2009: 6). This is a real ‘artificial coastline, formed by “military and diplomatic support points along the major shipping routes” (from Myanmar to the Strait of Hormuz), which enables China “to control and monitor the Indian Ocean” (Franco, 2007: 8). It is, therefore, due to the fact that Beijing has no technical or financial resources to ensure a permanent patrol far from the Chinese bases, that China had to negotiate such a project with the states bordering the Indian Ocean. The latter, being known as ‘String of Pearls’, might not only help increase Chinese soft power in peacetime, but also “to prevent piracy in time of war” (Chen, 2011: 2). Counting with bases in “Marao (Maldives); in the Cocos Islands (Myanmar); Chittagong (Bangladesh) and Gwadar (Pakistan)”, it is not to be ruled out that in addition to the strategy of the ‘String of Pearls’, Beijing also decides to “send troops to the African coast, which has shown itself to be increasingly receptive to Chinese investments” (Zajec, 2008: 13).

If New Delhi and Washington look with apprehension at the ‘facilities’ that Bangladesh or, for example, Pakistan have given to China’s strategy, it is, nevertheless, in Myanmar that it is seen as a threat to Indian and American interests. Besides the fact that from the Great Coco Island (Myanmar), it is “all traffic from the Singapore Strait, Indian maritime activities, including the missile test area of Chandipore, which can be monitored (by the Chinese)”, one must not underestimate, however, another issue (Xiaoquin, 2011: 14). This is, in fact, a “true revolution” because China would henceforth have “direct access to the Indian Ocean”, consisting of “a road and rail connection, coupled with a 1200 km pipeline linking the coast of Myanmar to the Chinese province of Yunnan” (Xiaoquin, 2011: 15). Certainly, despite being viewed with caution, or even concern by some countries, access to the Bay of Bengal is considered, however, essential by China. The Chinese are trying, indeed, to diversify their access to the energy resources as they fear that, in case of conflict, a disruption in energy supply might take place in the Strait of Malacca[1]. In addition to the pipeline project between Sittwe and Kunming[2], China’s strategy also emphasizes the development of a rail network that connects the ASEAN countries with each other. Finally, Beijing “supports the offshore production of liquefied natural gas in Southeast Asia, especially in Myanmar and Thailand”, as well the building of “a canal across the Kra Isthmus” (Zajec, 2008: 9). This last idea, which is indeed very old (“the first plans date back to the sixteenth century”), aims to create an “Asian Panama Canal (48 km)”, at a time when the “congestion and insecurity in the Strait of Malacca prove to be a very sensitive issue” (Wood, 2012: 11).

The new Chinese doctrine

In order to counter its navy’s technological backwardness relative to that of countries like Japan or the United States, China is gradually replacing the old coastal units by more modern ships. As Jean-Marie Holtzinger (2008: 2) points out, “the navy of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) seems to be a military instrument for Beijing which enables it to accomplish its regional ambitions and, at the same time, to place China among the great naval powers in the region”. As part of a regional approach, Beijing’s strategy aims, nevertheless, to make China become “a naval power in East Asia” (Holtzinger, 2008: 3). In addition, the fifth White Paper on China’s national defence published at the end of 2006 highlights the priority of modernizing the PLA Navy. In this regard, President Hu Jintao stated in late 2006 that “the Chinese navy should be strengthened and modernized (...) to better serve the motherland and the people” (Courmont, 2007: 18).

What we are witnessing today is a physical change (in the sense of an increasing modernization of military means), which is accompanied by an evolution of strategic thinking (Hong and Jiang, 2010). Both are, however, in interaction. As China becomes stronger militarily, it will dare ‘risk’ more because it knows it can then rely on its resources to do so. It would thus be able to gradually move away from its shores to conduct and/or support military operations in the open ocean. Inspired by the teachings of Sun Zi, the Chinese “only depart for battle when they are sure to win it” (Montbrial, 2000: 130). However, current events portray a China that is becoming more pragmatic, more secure and confident in itself. In addition, Chinese military strategy has changed its «operational thinking on attack submarines», because if once «they patrolled near the shore to prevent an invasion», currently «they are deployed to more distant waters in order to protect the sovereignty and maritime interests of the nation» (Hong and Jiang, 2010: 151). This bolder China has – like Russia, India, Iran, the United States, Japan and the European Union – also taken advantage, by sending its patrol vessels to the waters plagued by maritime piracy in the Indian Ocean. But, as pointed out by Tanguy Struye (2010: 8), «such a presence hides, however, another issue which goes far beyond the struggle against piracy: the domination of communication channels, because through this deployment, one notes there is a tacit struggle among the great powers to control the shipping lanes that go from the Strait of Bab el Mandeb[3] to the Strait of Malacca, arteries of world trade”. However, for the specific case of China, we have already explained above how Beijing – realizing that it lacked support points – expressed its ambition to build an artificial coastline (the famous ‘String of Pearls’) in the region. All this obviously proves China’s desire to project power, considering that it is a country that is not directly present in the Indian Ocean. Maritime piracy is, in this context, a useful argument for Beijing to more easily position itself in a region that is India’s natural sphere of influence (Cole, 2010).

The influence of the thinking of Alfred Mahan

Another aspect that should never be overlooked when one analyses China’s naval behaviour in this new century is closely influenced by the ideas of the American Alfred Thayer Mahan. For him, “the domination of the seas must be a priority given the freedom of the seas and the exploitation of the commercial maritime routes: trade needs a merchant marine and a navy to protect it, as well as support points (refuelling and reparation) on the waterways” (Struye, 2010: 12). However, if Mahan’s theories are not unknown by the naval doctrines of countries such as India and the United States, why do they increasingly attract the attention of Beijing? As already seen, China is becoming more pragmatic and confident in itself, daring to risk more (Wanli, 2010). This means, in operational terms, that Beijing is investing more and more in a sea denial strategy[4], moving thus gradually away from the mere defence of the Chinese shores. In the long-term, everything indicates that in twenty years, China will be able to form a blue-water navy.[5] Beijing seems, therefore, to have understand the need for a powerful naval force to protect the country; that a power that does not understand the importance of the oceans is a power without future; and that power that is incapable of defend its maritime rights will never be a maritime power for very long (Athwal, 2008).

Ensuring one’s power on the high seas implies having a word to say on the major issues that directly affect the vital interests of a state. The image one gives of itself is crucial because it influences the way powers respond to another power (though this does not mean that one’s perception of the capabilities of the other always corresponds to the real power of the latter) (Wanli, 2010).

Note that China’s strategy in this new century is not limited in any way to the defence of its borders. Instead, the Chinese borders of the 21st century henceforth also include the ‘borders’ of economic interests, vital for the harmonious development of an emergent superpower. In this regard, it is worth quoting the journalist H. Kulun (Liberation Army Daily, article of December 4, 2008) who confirms this idea: “Our armed forces need to defend not only ‘territorial boundaries’, but also ‘boundaries of national interests’ ... We need to safeguard not only national-security interests but also interests relating to future national development” (Struye, 2009: 11). It is within this context that we can understand Beijing’s concern in protecting commercial shipping lines.[6] In fact, China is well aware that to develop, it needs “new markets to export its products and import raw materials”, because as pointed out by W. Raleigh, “Whoever owns the sea, owns the world’s commerce, the world’s wealth: whoever owns the world’s wealth owns the world itself” (Struye, 2008: 12-13).

On the future: modernization vs. existing weaknesses

As we have noted, it is undeniable that China is gradually modernizing its fleet which will enable it to operate far from Chinese ports, thus giving rise to a ‘deep-water navy’[7].

It should, nevertheless, be stressed that there is a certain tendency to exaggerate the ‘China threat’ thesis which, by distancing itself from objectivity and serious investigation, turns out, however, to be more prone to fear and to other irrational feelings. One must be cautious because, according to Jean-Marie Holtzinger (2008: 11), “it is certain that the most alarmist messages and the overvaluation of Chinese power always come from the same sources of information, particularly Japanese ones”.

Notwithstanding, a realistic and objective analysis on the current capacity of the Chinese navy has highlighted several weaknesses, thus conflicting with certain authors’ forecasts, who believe that “by 2025 China could be the dominant power in the Pacific” (Holtzinger, 2008: 11). However, any assessment becomes more complicated when experts differ in their observations and conclusions. Thus, a relatively ‘optimistic’ vision about Beijing’s ability to rapidly strengthen its naval resources must be confronted by another, more ‘pessimistic’ vision, which does not hesitate to list some major difficulties. Let us point out, among others, “the important challenges that the Chinese must face with regard to financial resources and production of many modern ships, which is delayed by the obsolescence of the shipyards that have not been the object of any reform” (Xiaoqin, 2011: 9).

Furthermore, if the improvement of the Chinese navy is based, largely, on the purchase of ships and Russian-made military technology, it is important, however, to be aware of the “delay of Russian technology relative to Western technology” (Aggarwal, 2012: 20). On the other hand, “the Chinese army is an army of ‘two speeds; with the exception of a small hard core, poorly equipped and poorly trained” (Huasheng, 2009: 475).

Currently, the Chinese navy poses no major threat because “over half the navy is antiquated, even obsolete” and “if Beijing gradually develops its own defence industry, the embargo on offensive weapons which it has been subject to since the Tiananmen massacres hampers the PLAN (People’s Liberation Army Navy) modernization” (Aggarwal, 2012: 38). Improving the surface units involves the replacement of obsolete vessels, continuing to purchase Russian ships and the construction of Chinese-made Destroyers Class E 052B and 052C (using state of the art technology). Indeed, there are prominent weaknesses due to a lack of frigates and destroyers (which are specialized warships), but also of air defence means. As for underwater means, Beijing wants to modernize its fleet of diesel submarines, by replacing the already obsolete submarines of Soviet design. Regarding the production of submarines capable of launching missiles with nuclear warheads, China does not report a major advance (Wood, 2012).

Several rumours and speculation circulate around the launch of the first Chinese aircraft carrier. Notwithstanding, analysing the declarations made to the Chinese press in late 2008, it was possible to infer that “China is currently building its first military aircraft carrier that could be used in the South China Sea to protect the maritime routes of its oil tankers and its territories in the region”[8]. The source, a Chinese military expert, who, however, requested anonymity, stated that «the aircraft carrier would be conventional and of small dimensions (in comparison with the nuclear aircraft carriers of the United States), not being able to accommodate more than 60 planes» (Li, 2009: 23). In addition, the ship – that could «provide the air cover which China needs for its fleet (especially given the territorial disputes with other countries in the South China Sea)» – should not «surprise the international community», considering also that «India already has four of such ships» (Li, 2009: 24).

Despite the issues of disagreement between the various authors regarding the level of modernization of the Chinese navy, they agree, however, on the fact that around 2020 or 2025, the Chinese fleet would be much stronger than today (Ranade, 2009). Nevertheless, this is an ‘expected evolution’ given that China is a developing country that intends to protect the sea routes of energy supply, while ‘asserting its power’ in the international scene.

In conclusion, although the Chinese fleet «is still unable to deal with the U.S. Navy or confront, for now, some Asian navies, it is necessary, however, to consider the current expansion plans (along with a new naval doctrine) as a warning of what one can expect from China on security issues in the Pacific» (Castro, 2007: 5). But what will be the future of the ‘agitated’ waters of South-East Asia? As João Bertonha (2008: 21) mentions, «it is probably towards the shipyards that we must cast our eyes, if we want to know where the world is heading in the twenty-first century».

Sino-Indian power strategies in the Indian Ocean

Countries with a vast sea coast, the power play between India and China also encompasses, among other areas, the ocean. The latter is, in fact, crucial for two economies that are “rapidly growing and increasingly outward facing” as William Garnier (2005: 4) points out. It is by sea that almost 90% of the trade is carried out, but it is also the sea that ensures, to a very large part, the supply of fuel, vital to the economy of China and India. This means that it is not possible to speak of economic dependence without considering maritime dependence.

Given that the Strait of Malacca is a very sensitive transit point in Asian trade and that India and China are almost at the same distance from that strait, it is understandable that these two states “cannot simply ignore the problems of maritime security affecting their regional environment” (Hong and Jiang, 2010: 149). The fact that India has, according to J. Holslag (2008: 19), the ambition to “convert the Indian Ocean in an Indian Lake”, thereby declaring, according to Franco (2007: 6), “as its legitimate area of interest all the region of the Indian Ocean from the Persian Gulf to the Strait of Malacca”, can only arouse apprehension in Beijing. And all the more since the money spent by New Delhi in modernizing its navy has increased from 1.3 to 3.5 billion dollars in the period from 2001 to 2006 (Holslag, 2008: 15). Indeed, the Indian Ocean is to India its “natural security perimeter, from the Straits of Malacca to the Strait of Hormuz, and from the African shore to the coast of Australia” (Struye, 2010: 9). This explains why New Delhi has conducted, in recent years, a policy of approximation towards the Maldives, Seychelles and Mauritius which encompasses, among other aspects, maritime patrols, economic agreements and military training. Strengthening its ties with ASEAN, and its presence in the Gulf of Bengal, the Indian maritime doctrine is based on the Indira Doctrine (according to Indira Gandhi). In practice, this is a kind of Monroe Doctrine, applied to South Asia, and which finds its inspiration largely in the precepts set by Lord Curzon. Even though this author stressed the place of India within the British Empire, his ideas are not obsolete, but, instead, present in the vision that India currently has of its situation in South Asia (Batabyal, 2006).

A word about one, and the other fleet. If from a quantitative viewpoint it is China that has the largest navy, at a qualitative level, however, the Indians surpass the Chinese Navy, with a «more coherent, more modern and better trained navy» (Wanli, 2010: 4). One and the other present, however, a technology gap relative to the most modern fleets in the West (about 15 years for India and 20 years for China). Moreover, it is interesting to observe that the willingness to catch up to the West is such that, increasingly, India and China manage to build themselves modern ships, while limiting imports of sophisticated equipment. Notwithstanding, if the Indian navy can be seen as a ‘projection navy’, the Chinese navy is, on the contrary, essentially a ‘navy of interdiction’ («that is to say, with a potential to cause damage with its several submarines») (Aggarwal, 2012: 36).

If the infrastructures are, certainly, important, one should not overlook, however, naval diplomacy. This is the source of immense cooperation agreements that India has established with all the island states in the Indian Ocean (David, 2006). Indian maritime power is, therefore, searching for a nonviolent hegemony (with all that implies in terms of soft power), within a framework in which India is playing the role of ‘gentle policeman’ who expresses willingness in “keeping the ocean as a common good” (Holslag, 2008: 16). Nevertheless, if that naval diplomacy enables India to project its power, while creating a network of alliances in the region, it witnesses, at the same time, a suspicion against the maritime ambitions of other countries. China is a case in point. According to J. Holslag (2008: 22), “Indian naval diplomacy seeks to prevent China from launching its anchor in strategic locations ... (a fact that is) considered a major reason for the Indian offensive of naval charm”.

Nonetheless, while India is somewhat concerned with the ambitions of the Chinese navy, Beijing seems to be, in turn, concerned about the dilemma of energy security in the Malacca Strait. Indeed, the Chinese leadership believes that if an accident ever occurs in the strait, or if the latter is blocked by foreign powers, China could then see its energy supplies brought into question. However, Chinese officials are convinced that such a threat is more likely to come from powers such as Japan or the United States than from India itself (Ranade, 2009). Nevertheless, this does not mean that China has no interest in freeing itself from the domination of New Delhi over the Indian Ocean. Anyhow, as emphasized by Holslag (2008), a naval arms race with India is not likely, especially given that Chinese naval power will continue to pay more attention to Taiwan until a settlement is reached with the island. Moreover, the author adds that “China has no plausible legitimacy (except for the shipment of Zheng He in the 14th century) to explain to its neighbours why the Indian Ocean (contrary to the East and South China sea) must historically belong to its maritime area of interest” (Holslag, 2008: 25).

Taiwan

Strategic issues

The Taiwan question is crucial for China not only at the cultural, historical, economic, political and military levels, but also geographically and strategically. All these issues are, however, interrelated. This may also be viewed as a concern about prestige since, similarly to Hong Kong and Macao, Beijing also expects Taiwan to return to the People’s Republic of China. In fact, if the central authorities do not prove capable of achieving this return, it is their power that could then be seen as weak by the population. Failure in the return of Taiwan would mean, above all, a humiliation for Beijing, with other possible consequences, mainly over the credibility of the regime. Alan Wachman (2007: 153) mentions, in this regard, a ‘domino effect’ likely to spread “to Inner Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang”.

Taiwan is also important from a strategic viewpoint. In fact, if the island represents a major pawn in the strategy for control of the shipping lines, its return to the People’s Republic of China would also enable the Chinese to eliminate an American foothold in the region. Since the 1990s, China’s strategy with regard to the status of Taiwan has evolved into a more ‘warlike’ trend: Beijing is seriously considering leading a military intervention in the long-term. This helps explain why there has been, henceforth, a significant increase in the budget for defence, for the acquisition of weapons systems, at a pace that is viewed with concern by the Defence Department of the United States. According to the latter, «China has pursued military modernization, in the long-term, to improve its power projection and access denial capacity (...); in order to prepare itself for a possible conflict in the Taiwan Strait, China seeks to focus its most developed military forces in areas that surround the island”[9]. Without going further into details, one should stress that in 2006 China had approximately «710 to 790 SRBM”[10] pointed at Taiwan, and was considering (according to the Department of Defence) “using them for sea denial operations, intended to complicate the naval operations of its opponents, that is to say the U.S. or Japan, over Taiwan”; besides, China also had “400,000 units stationed near the island”[11]. Although the U.S. Department of Defence rigorously describe the Chinese military operational means (and those to be acquired in case of conflict in the Taiwan Strait), we confine ourselves here to observing the significant efforts made by Beijing over the last few years to modernize its armed forces. As Alan Watchman (2007: 16) indeed notes, China considers, since the last decade, that the People’s Liberation Army must be able to fight local wars under the most modern conditions.

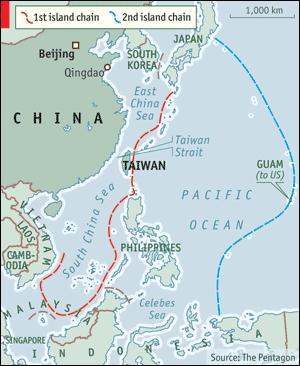

The question one must now ask is why Taiwan is (so) important for China, to the point that Beijing is willing to resort, if deemed “necessary”, to “non-peaceful means” (according to the Anti-Secession Law of 2005)[12]. From a strategic perspective, the non-return of Taiwan to China endangers the maritime ambitions of the latter, especially its desire to project power. More specifically, by controlling Taiwan, Beijing could henceforth control the coastal waters, by positioning itself on a belt of islands strategically located and used by the U.S., as a maritime hegemon, in order to counter the expansion of Chinese power (Wachman, 2007: 23). However, for now, China is experiencing a feeling of impotency, even of indignation due to the status of Taiwan, but also because of the alliances and the strengthening of collaboration between the U.S. and the countries of the region. Certainly, the U.S. 7th Fleet is, somehow, a balancing factor for the region given the double deterrence effect it has with respect to the use of force by Beijing and the proclamation of independence by Taiwan. It also offers protection to countries such as South Korea, India and Indonesia, among others. Nevertheless, all agreements and alliances forged by Washington (especially with Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei and Malaysia) are perceived by China as dangerous with regard to its maritime strategy[13].

If Beijing proves to be able to control Taiwan, it would henceforth dominate two crucial passages, namely the Taiwan Strait and the sea lines of communication to the east of the island. Otherwise, China believes its business interests might be endangered, vulnerable to hostile actions, such as maritime blockades (Rahman, 2001). Another reason for the strategic importance of Taiwan and all the surrounding passages is that their control would allow the deployment of a credible nuclear deterrence force with regard to the United States. This force depends on the ability of China to «launch a nuclear strike against targets located in the continental United States (capacity at its disposal thanks to ICBM[14]), but also on the ability to survive a U.S. nuclear strike and to respond with a second strike” (Wachman, 2007: 147-148). To deliver such a strike, foreign experts suggest that China is considering resorting to nuclear missile-launching submarines. Notwithstanding, given that Beijing does not yet have powerful enough submarines to launch this second strike, the latter need, therefore, to move beyond the ‘first island chain’ to get into position.

However, there is yet another barrier. According to Peter Howarth (2006: 35), “the problem for China is that the submarines cannot reach the high seas without passing through the bottlenecks formed by the chain of islands that enclose the coastal waters of China”. Also according to this author, «the control of these islands by the Asian-American security network partners enables the United States to establish, at a distance, a blockade of the Chinese fleet, in order to counter power projection beyond its continental bases» (Howarth, 2006: 35).

That said, why is Taiwan strategically important for China? Because, once the latter is under Chinese control, all the passages around the island would not continue to be a problem for its maritime ambitions. And, moreover, Chinese submarines would no longer be forced to expose themselves to ‘enemy control’[15] in the passages of the Taiwan Strait (whose average depth is 100 meters), and in addition they could launch into the sea from the eastern coast of Taiwan (where the water is 4,000 meters deep) (Wachman, 2007). If the island were dominated by Beijing, the Chinese submarines would henceforth have the opportunity to go more unnoticed, in order to reach areas of the central and eastern Pacific, from which their strike force would be finally able to reach the territory of the United States (Ranade, 2009).

Conclusion

Americans, but also Japanese, Russian and Indian, among others, watch, with apprehension, the modernization of China’s armament, especially of its navy.

What does Beijing expect from the sea? As we have seen, the Chinese naval position, in this new century, is closely influenced by the ideas of the American Alfred Thayer Mahan. China seems, indeed, to have understood what the United States and other maritime powers have already known for a long time: trade implies a merchant marine and a navy to protect it, as well as support points (refuelling and repair) along the waterways. Similarly, Beijing has internalized that a power that does not understand the importance of the oceans is a power without future. In this sense, China is aware that its future is, to some extent, mapped out in the waters. Otherwise, one could not understand why it is imperative for Beijing to protect the sea lines of trade (the ‘pearl necklace’ strategy is quite illustrative in this regard), but also to project its power on the ocean. Taiwan is obviously a major issue, because of the strategic importance of the island. Nevertheless, it is basically a piece in the complex puzzle of islands, islets, archipelagos and other critical sea passages, encompassed by the Chinese maritime strategy. As China becomes more confident of itself, it is likely to invest in a strategy of sea denial, thus moving gradually away from the simple defence of the Chinese coast to build, in the long-term, a navy capable of operating on the high seas.

References

Aggarwal, Shikha (2012). “China’s Naval Strategy: Strategic Evolution and Emerging Concepts of Warfare”, Air Power Journal, Vol. 7, no. 2.

Athwal, Amardeep (2008). China-India Relations. Contemporary Dynamics, London & New York: Routledge.

Batabyal, Anindya (2006). “Balancing China in Asia: A Realist Assessment of India’s Look East Policy”, China Report, Vol. 42, no. 2.

Bertonha, João (2008). China e Estados Unidos : rivalidades geopolíticas e a questão militar, Boletim de Análise de Conjuntura em Relações Internacionais, available at www.meridiano47.info/2008/04/16/china-e-estados-unidos-rivalidades-geopoliticas-e-a-questao-militar, accessed 20/09/2012.

Buszynski, Leszek (2012). “Chinese Naval Strategy, the United States, ASEAN and the South China Sea”, Security Challenges, Vol. 8, no. 2.

Castro, Luiz (2007). China reforma e expande a sua marinha, Conjuntura Internacional, available at www.pucminas.br/imagedb/conjuntura/CNO_ARQ_NOTIC20070523111946.pdf?PHPSESSID=ee7d9e27f570426fb80daa1c5ef413fb, accessed 01/10/2012.

Chen, Dean (2011). “Sea Power and the Chiese State: China’s Maritime Ambitions”, Backgrounder, no.2576.

China constrói seu primeiro porta-aviões militar, Agência EFE, 2008, available at www.noticias.terra.com.br/mundo/interna/0,OI3338081-EI294,00.html, accessed 30/10/2012.

Chine: texte intégral de la Loi anti-sécession, Ambassade de la république Populaire de Chine en France, available at http://www.amb-chine.fr/fra/xnyfgk/t187623.htm, accessed 30/10/2012.

Cole, Bernard (2010). The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy in the Twenty-first Century, 2nd edition, Annapolis Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Courmont, Barthélémy (2007). Le nouveau Livre blanc sur la défense de la Chine, Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques-France, available at www.iris-france.org/docs/pdf/regardtaiwan/2007-01-05.pdf, accessed 10/10/2012.

David, Scott, (2006) “India’s Grand Strategy for the Indian Ocean: Mahanian Visions”, Asia-Pacific Review, Vol. 13, no. 2.

Franco, Élodie (2007). La Chine renfloue sa marine pour asseoir ses ambitions régionales, Ministère de la Defense, available at www.defense.gouv.fr/defense/ada/la_chine_renfloue_sa_marine_pour_asseoir_ses_ambitions_regionales, accessed 15/10/2012.

Garnier, Guillaume (2005), Les enjeux de la compétition maritime entre l’Inde et la Chine, Institut français de géopolitique, available at www.cedoc.defense.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/RESUME_INDE_CHINE_GARNIER_1_.pdf, accessed 16/10/2012.

Holslag, Jonathan (2008). “China, India and the Military Security Dilemma”, Biccs Asia Paper Vol. 3, no. 5.

Holtzinger, Jean-Marie (2008). Escalade des tensions entre la Chine et les Etats-Unis en mer de Chine méridionale, Géostratégie, available at www.geostrategie.com/962/escalade-des-tensions-entre-la-chine-et-les-etats-unis-en-mer-de-chine-meridionale, accessed 16/10/2012.

Hong and Jiang (2010). “China’s Strategic Presence in the Southeast Asian Region”, in Forbes, Andrew (ed.), Maritime Capacity Building in the Asia Pacific Region, Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs No. 30, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Howarth, Peter (2006). China’s Rising Sea Power: The PLA Navy’s Submarine Challenge. New York: Frank Cass.

Huasheng, Zhao (2009). “Central Asian Geopolitics and China’s security”, Strategic Analysis, Routledge, Vol. 33, No. 4, July.

Kenny, Henry (2004). “China and the competition for oil and gas in Asia”, Asia Pacific Review, Vol. 11, no.2.

Li, Nan (2009). “The Evolution of China’s Naval Strategy and Capabilities: From ‘Near Coast’ and ‘Near Seas’ to ‘Far Seas”, Asian Security, vol. 5, no.2.

Medeiros, Roberto (2007). Reflexões sobre as ambições marítimas da China na actualidade, Geoatlas, available at www.sagres.org.br/biblioteca/ambicoes_china_01.pdf, accessed 20/10/2012.

Montbrial, Thierry de (2000). Dictionnaire de Stratégie. Presses Universitaires de France.

Rahaman, Chris (2001). “Defending Taiwan, and Why it matters”, Naval War College Review, Vol. LIV, No.4, Autumn.

Ranade, Jayadeva (2009). “The Implications of China’s Navy Modernisation”, Air Power Journal, Vol. 4, no.4, Winter.

Rizzi, Andrea (2009). China e Índia disputam o Indico, El Pais, available at www.noticias.uol.com.br/midiaglobal/elpais/2009/03/19/ult581u3114.jhtm, accessed 20/10/2012.

Struye, Tanguy (2008). China and World Politics, Dossier de Lecture, Louvain-

-la-Neuve: Diffusion universitaire CIACO.

Struye, Tanguy (2009). La Chine et le «Soft power»: une manière de défendre l’intérêt national de manière «douce»?, Chaire InBev Baillet – Latour Programme «Union Européenne – Chine». Louvain-la-Neuve: CIACO.

Struye, Tanguy (2010). La piraterie maritime: un nouveau rapport de force dans l’Océan indien ?, Chaire InBev Baillet – Latour Programme «Union Européenne – Chine». Louvain-la-Neuve: CIACO.

Struye, Tanguy (2011). Offensive chinoise en Afrique, Chaire InBev Baillet – Latour Programme «Union Européenne – Chine». Louvain-la-Neuve: CIACO.

U.S. Department of Defense, Military Power of the People’s Republic of China, 2006: A Report to Congress Pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act Fiscal Year 2000, available at www.defenselink.mil/pubs/pdfs/China%20Report%202006.pdf, accessed 22/10/2012.

Wachman, Alan (2007). Why Taiwan? Geostrategic Rationales for China’s Territorial Integrity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Wanli, Yu (2010). “The American Factor in China’s Maritime Strategy”, in Erickson, Andrew, Lyle J. Goldstein and Li, Nan, China, the United States, and 21st Century Sea Power, Annapolis, Maryland Naval Institute Press.

Wood, Michael. (2012). Chinese Maritime Power – Is the increase In China’s maritime power internally consistent with China’s national interests and foreign policy, or cause For concern?, Royal College of Defence Studies, SEAFORD HOUSE PAPER.

Xiaoqin, Shi (2011). “An Analysis of China’s Concept of Sea Power”, ASIA PAPER, Institute for Security and Development Policy, December.

Zajec, Olivier (2008). A China quer os mares, Geopolítica, Le Monde diplomatique, available at http://diplo.uol.com.br/2008-09,a2602, accessed 29/10/2012.

[1] The Strait of Malacca is a vital crossing point. Indeed, more than 60,000 ships cross the strait every year, which means that 25% of oil and 2/3 of gas pass through this artery. As alternatives to the Strait of Malacca, there is the Sunda Strait (whose lack of depth does not allow the passage of large ships) and the Lombok Strait (although it is easily navigable, it increases voyage times by three or four days). If there is an obstruction of such straits, vessels are then required to pass along the coast of Australia, which has the disadvantage of extending the journey by an additional 15 days.

[2] Sittwe is located on the western coast of Myanmar. Kunming is a port of Yunnan in southern China.

[3] The strait separates the Arabian Peninsula from Africa and connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden, in the Indian Ocean. It represents not only an important and strategic location but also one of the busiest sea lanes in the world.

[4] Sea denial is a military term that describes the attempts to deny an enemy the ability to use the sea (typically through naval and/or port blockades). This is a strategy much easier to implement than that of sea control since it requires the mere existence of a navy.

[5] The term blue-water navy means a naval force capable of operating in deep waters of open oceans. In other words, it is the ability to operate a fleet on the high seas.

[6] About 90% of China’s trade passes through the sea, of which 22% is to the European Union and India.

[7] One uses the term ‘deep-water navy’ to indicate that a navy is able to operate beyond the shore, in deeper and remote waters and, with the ability to undertake efficient operations.

[8] China constrói seu primeiro porta-aviões militar, Agência EFE, 2008, available at www.noticias.terra.com.br/mundo/interna/0,OI3338081-EI294,00.html, accessed 30/10/2012.

[9] U.S. Department of Defense, Military Power of the People’s Republic of China, 2006: A Report to Congress Pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act Fiscal Year 2000, available at www.defenselink.mil/pubs/pdfs/China%20Report%202006.pdf, accessed 22/10/2012.

[10] SRBM: Short-range ballistic missile.

[11] U.S. Department of Defense, Military Power of the People’s Republic of China, 2006, Op. Cit..

[12] Chine: texte intégral de la Loi anti-sécession, Ambassade de la république Populaire de Chine en France, available at http://www.amb-chine.fr/fra/xnyfgk/t187623.htm, accessed 30/10/2012.

[13] Moreover, the United States have bases (or privileged accesses) in Japan, Guam, the Philippines, Singapore, as well as alliances with Australia and New Zealand, which represent serious obstacles to any Chinese attempt of competing with the U.S. naval superiority.

[14] ICBM: intercontinental-range ballistic missile.

[15] In addition to the very low depth and narrow passage, the Taiwan Strait can be a complicated place for strategic manoeuvres of Chinese missile-launching nuclear submarines because of the strong oversight over them. In fact, these submarines can be endangered by a set of devices that might detect their presence, some of which are related to database handling systems, located at the seaside (Wachman, 2007: 149).